Arsene Wenger has given his personal recommendation that could allow Freddie Ljungberg to follow in his footsteps and manage in Japan.

Freddie Ljungberg is a ‘serious contender’ for the managerial poison that is currently vacant at FC Tokyo, who are currently 9th in the J League. While FC Tokyo are not the betting favourites with bettingsidor.se or other Swedish bookmakers to win the J League, they still represent an interesting career path for the former Arsenal star.

Ljungberg’s only top managerial role came when he stepped in following the sacking of Unai Emery.

He took charge of six games, only one of which Arsenal won, although we can hardly hold that against Freddie given the state of Arsenal at that time.

Beyond that, he has served as assistant manager at Arsenal and Wolfsburg as well as the Arsenal u23 manager.

Ljungberg is said to be giving the position consideration as he ponders moving into full-time management.

FC Tokyo

FC Tokyo’s manager, Kenta Hasegawa resigned from his job after his side were trounced 8-0 by Yokohama Marinos and guiding them to 14 wins, 14 defeats and seven draws this season.

The club was founded in 1935 as Tokyo Gas SC but rebranded in 1999 as FC Tokyo, eight years after they first made an appearance in the national leagues.

FC Tokyo traditionally play in a kit that is reminiscent of Crystal Palace’s red and blue stripes, at least it did when the Eagles had straight stripes rather than the diagonals they are sporting this season.

That being said, the designers have taken a few liberties with FC Tokyo’s shirt this season, too:

FC Tokyo have only two players valued at more than £1m.

Diego Oliveira, a 31-year-old Brazilian centre-forward who previously played for Kashiwa Reysol, Associação Atlética Ponte Preta and Boa Esporte Clube (MG).

The other is 30-year-old Brazilian-Italian centreback, Bruno Unvini, who spent some time with Tottenham’s reserves, as well as appearing for Napoli, Sao Paulo, Santo, Al-Wakrah SC, Al-Ittihad Jeddah, FC Twente and Al-Nassr Riad.

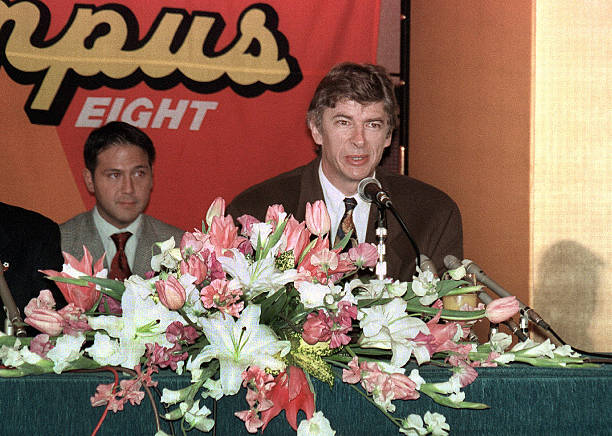

Wenger at Nagoya Grampus Eight

Before joining Arsenal in 1996, Arsène Wenger spent a couple of years in Japan, managing Nagoya Grampus Eight.

Wenger had decided to leave France after his sacking by Monaco, with worries about the integrity of the game in the country. #

Marseille had been found guilty of match fixing in 1994, and Monaco had been one of the teams affected the most by the scandal. But it wasn’t clear where he would go next. Toyota, who owned Nagoya Grampus Eight, met with Arsène and made him an offer to join the club, although the opportunity clearly didn’t immediately take the Frenchman’s fancy.

It took two months of deliberation, consultation with friends and family, and a trip to Japan to watch the team live, before he finally made his decision. So it was only in December 1994 that Wenger agreed to become manager of the side.

Although football in Japan has never reached the same level of popularity it has in some countries in Europe, there wasn’t a complete disconnect between the two footballing communities. Gary Lineker, for example, moved from Spurs to Nagoya Grampus Eight in 1991, and remained until 1994, playing his final match as Wenger watched on.

It was very much at the end of his playing career, but nonetheless it shows that Wenger’s move from Europe to Japan wasn’t completely unprecedented.

Despite Lineker’s presence in the team, Nagoya Grampus Eight hadn’t been very successful at all in the 1994 season.

The J. League was split up into two stages, with all twelve teams playing each other twice in the first stage (home and away) and then twice again in the second stage. The team that finished top in the first stage would play against the team that came first in the second, with the winner becoming the league champion.

There was no danger of Nagoya Grampus Eight taking part in the championship match that year, as they finished 8th in the first stage and 12th (or last) in the second. No wonder they wanted a change of manager, but clearly Arsène would have his work cut out for him.

Fortunately, the new J. League season wasn’t set to kick off until March, so Wenger had a few months after his appointment to set things up for the new campaign.

The first man he turned to was Boro Primorac, a former defender who had gone on to manage Cannes and Valenciennes in France. He wanted Primorac as an assistant manager, after becoming friends with him during the aforementioned match-fixing scandal.

When Primorac was still with Valenciennes, one of his players told him that he and two team-mates had conspired to throw a match against Marseilles. Marseilles president Bernard Tapie tried to buy Boro’s silence, but the Bosnian ignored his attempts and gave evidence to the courts that ended up seeing Tapie jailed and Marseilles’ Champions League title taken away from them.

Unfortunately, rather than this being seen for the brave action that it was, many people in France thought Primorac had broken a code of silence in football. Valenciennes ended up sacking him and he reportedly felt personally threatened by the situation.

Unlike many others in French football, Arsène Wenger greatly admired what Boro had done. Wenger publicly supported him at the time, and on leaving France made this job offer to be his assistant, which would allow Primorac to continue his career in management, rather than seeing it come to an early end.

If you’re an Arsenal fan and you recognise Primorac’s name, that’s likely because the 63-year-old still works alongside Arsène Wenger today. He doesn’t sit with the boss on the bench, instead taking his place in the stands, watching the game, and bringing his tactical observations to Wenger at half-time and at the conclusion of the match.

Bob Wilson once called Boro “an encyclopedia of world football”, and he’s been Arsène’s main man for discussions on players, tactics and team selection behind-the-scenes for the 23 years since. It says something about how much Wenger values loyalty and integrity, that he would keep the coach around for so long, but it’s also revealing about the manager’s approach to matches. The 68-year-old knows he can’t see everything from the bench, he knows he can’t call everything correctly on his own, so he has someone watching the game from a different perspective, to help him get new insights.

At Nagoya Grampus Eight, however, the pair’s working relationship was still in the early stages, and Boro did sit alongside the Frenchman on the bench.

Wenger then moved onto signings on the pitch.

He signed Brazilian centre-back Alexandre Torres from Vasco da Gama in the Campeonato Brasileiro Série A. Arsène scouted him by watching Brazilian football on TV, a tactic which was much less popular back then, compared to now, when video clips are commonly utilised by scouting departments.

Arsène also signed a couple of players from Ligue 1, with Franck Durix joining from Cannes and Gerald Passi from Saint-Etienne. Both players were midfielders, and Passi had previously played under Wenger at Monaco.

Unfortunately, the new signings on and off the pitch weren’t a magic fix for the team that had placed so poorly in the previous season’s table. There was still a lot of work to do, and that was evident from the team’s early performances, as they lost several matches in a row. Wenger was reportedly often frustrated with his players at these early stages, and when some of them asked what they should be doing in training, he’d respond: “Decide for yourself. Why don’t you think it out?”

The side were certainly improving, however. After the initial poor start, they ended the first stage of the campaign in fourth place. Nonetheless, Wenger still thought there was room for improvement. In the mid-season break, he took the team to Versailles, in France, for a 14 day training regime to increase their mental strength and to teach them to be more creative.

Clearly the mid-season training camp was very effective, as Grampus Eight won their next ten home games when the J. League season resumed. In particular, Dragan Stojković, who had previously struggled to stay disciplined, found himself much more focused under Wenger, and he became one of the best players in the league that season.

Nagoya Grampus Eight made it all the way up to second place in the table by the end of that first season, just missing out on the championship match, but finishing above Yokohama Marinos, who had won the first stage. Arsène was named manager of the year for his league exploits in turning the team around, and Dragan Stojković received the double award of being in the league’s best eleven, and being named Most Valuable Player.

The side also started to put together a run in the Emperor’s Cup, getting better as the competition went on. By the end, they were blowing away their opponents, winning the semi-final 5-1 against Kashima Antlers, and the final against Sanfrecce Hiroshima 3-0. The club has won their first ever piece of silverware, and Wenger had left his mark on their history books.

Not only that, but the silverware represents the continuation of Arsène’s cup success over the years. At Monaco, he’d won the Coupe de France, and at Arsenal he’s now the record holder for most ever FA Cup wins as a manager, with seven trophies. Clearly there’s something about the cup competitions that helps Wenger’s teams be a level above the competition so regularly.

Not long after that Emperor’s Cup, Arsène had the chance to help the club to their second piece of silverware. As in most countries with a football league and cup, Japan has a Super Cup, and Nagoya Grampus Eight took on J. League champions Yokohama Marinos in front of nearly 40,000 fans at the Tokyo National Stadium in March 1996. Two first-half goals were enough to seal a 2-0 victory and another cup to put in the trophy cabinet.

A week later, it was time for the J. League to get underway for another season. The league was undergoing some changes, which saw a number of new teams introduced, and the split season format scrapped. Whilst the system of playing four matches against every team wasn’t so hectic when there were only 12 teams in the league, it was more of a push with the 14 teams in 1995, and by 1996 there were 16, which would have meant 60 matches in the old system.

Instead, the number of games was dramatically reduced to just 30, as each side only played each other twice, home and away. Rather than the winner of each stage playing each other in a championship game, the team in first after 30 games just won the title. So it was much more similar to the majority of top leagues around the world today.

Grampus Eight made a great start to the season, winning seven out of the first eight games and even sitting top of the league on a couple of occasions. But a run of four losses in the next six games gave them a lot of work to do to, to get back to the top. Nonetheless, they went into the summer break and the J. League Cup in fifth place, which wasn’t the worst situation to be in.

Their J. League Cup form was significantly worse, however. Grampus Eight went on a nine-match streak without a win, although they followed that up with a couple of 6-1 victories in the final games of the competition. But they finished seventh out of the eight teams involved overall.

Despite the team’s poor form, Arsène Wenger was getting a lot of attention from European teams. Strasbourg enquired about his availability, and of course David Dein made the manager an offer from Arsenal. Dein had previously tried to convince the board to hire Wenger the previous year, but hadn’t been successful. Throughout that year, he sent Arsène match tapes for analysis, to get his opinions on how the Gunners were playing. Clearly David was impressed with the responses he was getting, enough to ignore Wenger’s current club’s poor spell.

Eventually, Dein managed to get the board to change their mind on Wenger, as the Gunners weren’t doing particularly well at the time. He then got Arsène to agree to be part of the Arsenal project, and the wheels were set in motion for the boss’ next chapter.

Unfortunately, Wenger was still under contract in Japan, and it was a contract he intended to honour until Nagoya released him from it. So that meant continuing to manage the side as the J. League resumed. Between the league getting back underway and Arsenal’s announcement of their new manager, Grampus Eight won six matches in a row, making their way up the table into second place. Wenger said his goodbyes, giving a farewell speech to the fans at the stadium in Japanese, and left to join the Gunners.

Nagoya wouldn’t manage to win the league in the end, but Arsène had taken them from dead last to second from the top, in a couple of years. He’d also given them their first taste of trophy success. In fact, Wenger’s legacy at the club sprung up again years later, when his star forward Dragan Stojković returned as manager in 2008. Stojković, who owed so much of his career progression with Grampus Eight to Arsène, led them to their first league title 2010.

Before that, Wenger did briefly make a return to the country in person, though it was only to commentate and provide punditry for the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup.

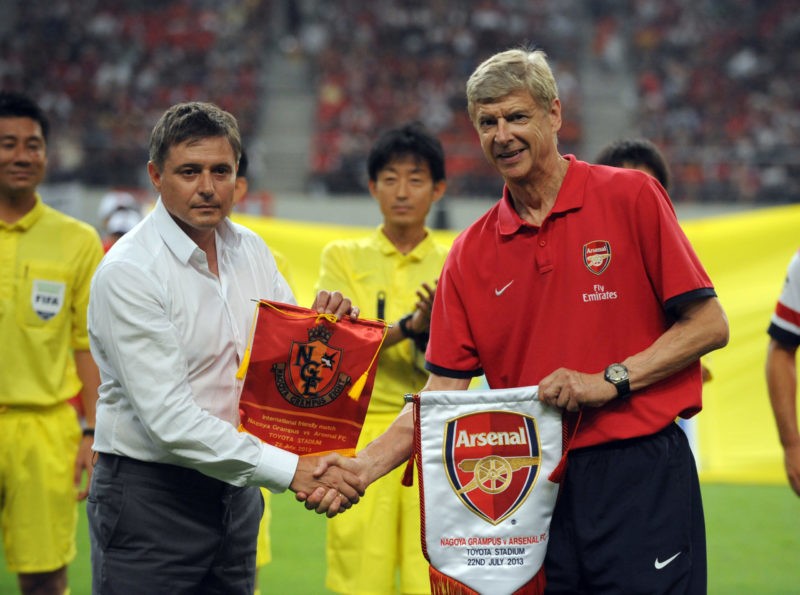

10 years later, in 2013, Wenger took an Arsenal side including Olivier Giroud, Theo Walcott and Per Mertesacker to take on Nagoya in a pre-season friendly. Giroud opened the scoring, before Japanese international Ryo Miyaichi pleased both sets of fans by doubling the Gunners’ lead. Miyaichi grew up in the local area, so he represented another connection between the two. Walcott added a third, and Kisho Yano got a consolation goal as the match ended 3-1.

In choosing to play this match, Arsène showed he hadn’t forgotten his old club, and the sold out 45,000-seat stadium suggested the fans hadn’t forgotten him either.

The culture in Japan also had an impact on Wenger’s management style, as he explained in an interview in his early years at Arsenal. He told reporters in 1997: “It is a basic rule of the job never to react when you are upset. But it is a difficult thing for me. The easy thing is to shout a lot.

“When I started, I was very emotional. I made many mistakes by reacting to things too quickly. I was sent off when I was manager of Monaco for shouting at the referee.

“Afterwards, you’re so sorry. You realise you’ve done so much damage you cannot repair. You spend so much energy trying to repair those mistakes when the main thing is to understand what’s really important.

“It helped me a lot to go to Japan, where I was manager of Grampus Eight. Everybody there is controlled. They laugh at you if you show emotion.”

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why Wenger can so often be seen sitting on the bench while his opposing counterpart jumps around on the touchline. Although Arsène is a lot more prone to emotional outbursts these days, than he was during the early years at Arsenal.

Another element of Japanese society that the Frenchman seems to have incorporated into his management style is a focus on diet. Wenger noted during his stay that although Japanese people work hard, they nonetheless have a very long life expectancy. He put this down to their diet, and their focus on living healthily in general.

When Arsène came to England, he’d obviously taken this on board. “I think in England you eat too much sugar and meat and not enough vegetables” Wenger once told a reporter. He then changed the diet of his players, to a lot of opposition at first.

“I changed a few habits of the players, which isn’t easy in a team with an average age of 30 years – at the first match the players were chanting, ‘We want our Mars bars!'” Wenger recalled. “At half-time, I asked my physio Gary Lewin, ‘Nobody is talking, what’s wrong with them?’ He replied, ‘They’re hungry.’ I hadn’t given them their chocolate before the game. It was funny.”

The last thing Wenger seems to have brought to the Gunners from his days in Japan is a love and appreciation of beauty in life. He once said that the country “has beautiful things that we have lost in Europe, beautiful things that make life good”.

Perhaps that’s why Arsène has such an idealistic view of football. He talked at the 2017 Arsenal AGM about wanting to win playing beautiful football, whilst respecting the traditions of the past and bringing through the players of the future. Most managers are content just to win. Tradition and beauty are clearly held in higher regard in Japan, so maybe that’s where Wenger gained the belief that a modern society and a modern game could still survive and be successful whilst respecting and cultivating these traits. His time in Japan may have been brief, but I think it’s clear that we’re still seeing its influence today.

Freddie Ljungberg: Model, man, manager

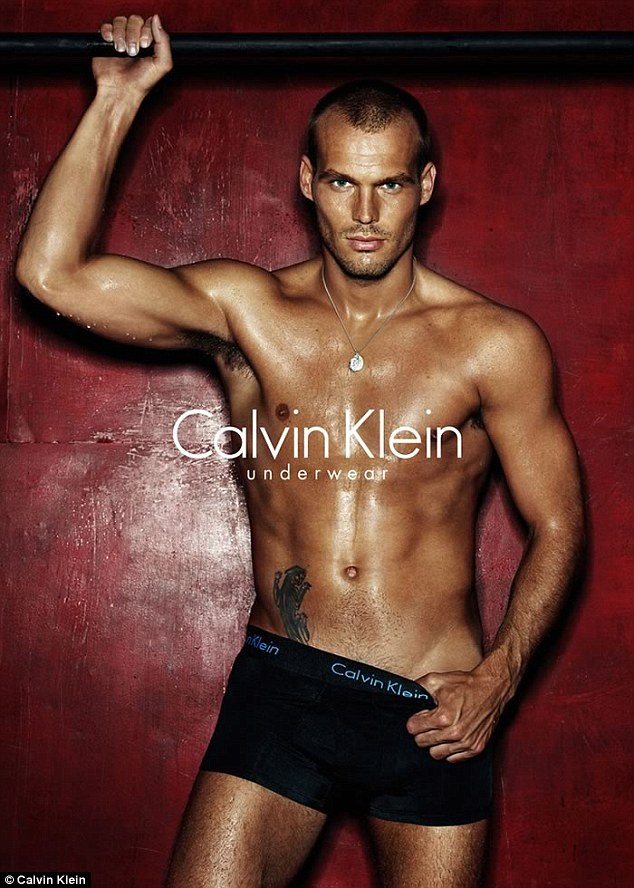

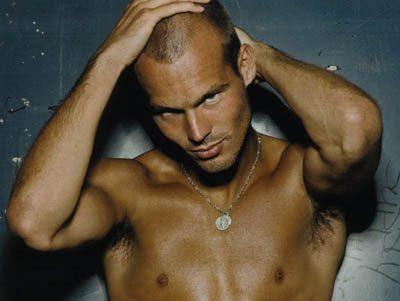

15 years ago, a Swedish Calvin Klein model named Freddie Ljungberg crowned a distinguished career in front of the camera with the receipt of a prestigious and much-coveted award.

Vittsjö-born Fredrik Ljungberg, a noted specialist in underwear shoots, was voted by readers of highbrow quotidian The Sun as “The Sexiest Player in the Premier League”. The victory was a tour-de-force for this chiselled doyen of male mannequins, the culmination of a glorious period in the limelight and recognition of his peerless dedication to the cause of bodily perfection.

Over the preceding years, cheekbones hoisted higher than a Chris Waddle penalty and an abdomen as finely sculpted as that of a Greek god had catapulted Freddie rapidly to the pinnacle of his trade. He became a household name, with his torso, groin and occasionally face gracing billboards across the world.

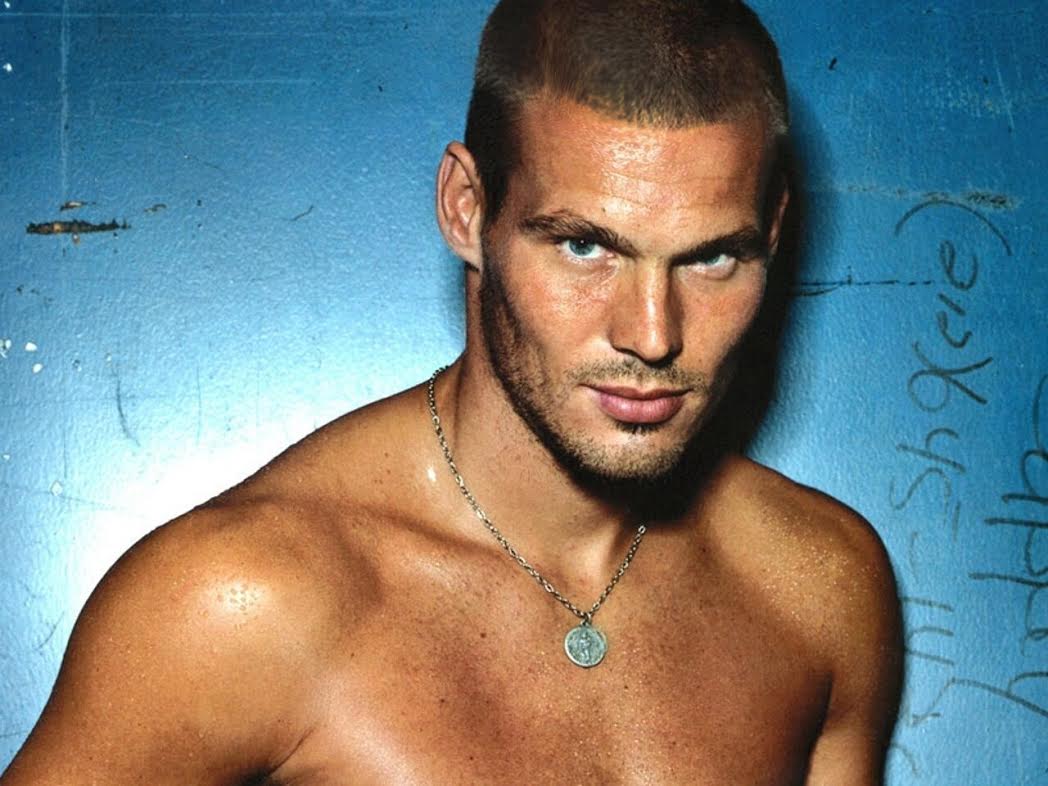

But, despite his success, life wasn’t always a breeze for the Scandinavian pinup.

“It sounds so cocky and I will not whine, but if, for example, I’d go to a night club, girls would come up and grab my crotch,” he revealed to Swedish paper Di in a heartbreaking exposé.

“Just like that. It was happening everywhere. They came from behind, side, pulled and tugged at me. The worst part was that you could not do a damned thing about it. When I angrily removed my hands, people just laughed. Some people thought that I could blame myself, I had done Calvin Klein and played for a top team…”

Arguably, Ljungberg’s side-job as a professional footballer for the aforementioned “top team” may have ultimately hindered his modelling career, but there is undeniable proof he was very good at it.

Almost a decade after emerging triumphant in the Sun poll, the Swede was acknowledged as being the eleventh-greatest player in the history of Arsenal FC, a modest London-based outfit who had repeatedly insisted on his participation in their activities despite being aware of his obligations to the world of fashion.

We all know the story of Freddie the globetrotting model;.

Here’s the lesser-known story of Freddie Ljungberg the footballer.

When Ljungberg and his jawline turned up at Highbury in September 1998, very few in the UK had heard of him. But those were the days when Arsène Wenger’s reputation as a finder and polisher of hidden footballing diamonds was approaching its peak.

He’d already succeeded in transforming the likes of Emmanuel Petit, Nicolas Anelka and Patrick Vieira from inconnus into international stalwarts and believed he’d spotted similar potential in Ljungberg.

And he was right.

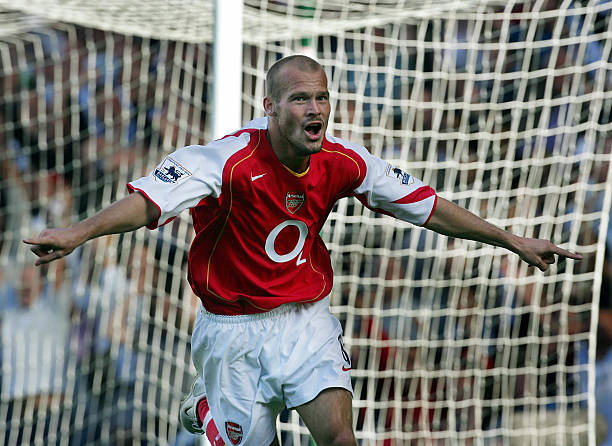

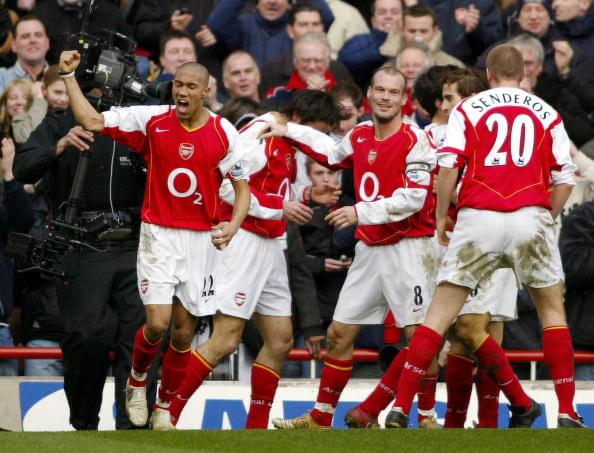

The Swedish midfielder swiftly won the hearts of both his manager and the club’s fans with a unique brand of aggressive, box-to-box play. Within months of his arrival, the supporters were entirely smitten, observing with rapt attention as Ljungberg approached each game with an almost manic sense of urgency, haring about the pitch with a barely restrained fervour.

When in defence, he sought the ball with the hungry air of a truffle-hog pounding through a forest, the scent of a tuber in its nostrils.

In attack, he was pure zealot, a mohawked kamikaze casting himself with abandon at the opposition. Onlookers swooned as they watched him chop at an opponent’s heels and win back possession twenty yards from his own goal, before gaping in awe as he charged the length of the field on the counter, smoke pluming angrily from his heels.

Yet there was an element of control about Ljungberg’s play, a ruthless internal calm that belied the sheer ferocity of his running.

He could finish with a coldness that surprised you: shots on the run curled with precision into the bottom corner; dinks over and around onrushing keepers; low, skimming drives rasped in from the edge of the box.

Such a proficient and composed finisher did he become that he ended up with 72 goals for Arsenal, many of which arose from his knack of zipping beyond the forwards to get on the end of crosses, touches and through balls from Pires, Bergkamp or Henry.

But it wasn’t just in front of goal that Ljungberg showed his poise.

There were madcap dribbles and rapid dragbacks carried out with arms thrashing and legs splaying, yet with the ball remaining throughout nestled safely on his instep.

There were raking passes, glancing clips that bisected backlines and a variety of improvised first-time nudges, all executed with a precision that seemed at odds with his often-frantic movements.

Ljungberg was busy, a harum-scarum one-man hive of activity. But so often, it was his technique that punished his foes: he had that rare ability to paralyse opponents with a flash of skill or flair for which they weren’t prepared.

The sense of perpetual motion that he projected sometimes gave the impression of a certain lack of refinement in comparison with some of his more ostentatiously gifted team-mates, but this served only as a distraction: those who underestimated his talent usually paid for their complacence.

And so, while that famous 2007 Sun accolade remains unquestionably his finest achievement, it should be acknowledged that Freddie managed to become one of the most enduring icons of the Invincibles era, not just for his committed play but also for his endearing quirks: the gaudy fauxhawk, the tattoos, the easygoing charm.

Ljungberg was also one of the most effective Premier League players of his era, an unassuming, reliable figure who combined physique, hard work and talent to cement his place at the heart of – perhaps – the competition’s greatest ever team.