50 years ago today, on 11 June, 1971, Liam Brady joined Arsenal’s Academy, so we take a long look back at his time at the club as a player.

“I had never felt so intensely about an Arsenal player,” wrote Nick Hornby in Fever Pitch. “Liam Brady was one of the best two or three passers of the last twenty years, and this in itself was why he was revered by every single Arsenal fan, but for me there was more to it than that. I worshipped him because he was great and I worshipped him because, in the parlance, if you cut him he would bleed Arsenal… but there was a third thing too. He was intelligent.”

Make no mistake, Liam Brady was the best player to have appeared in an Arsenal shirt between the all conquering team of the 1930’s and Dennis Bergkamp who found his peak form in the 1998 double winning side. He is the most talented player to come through the Arsenal youth system, and probably the finest player his country has ever produced. He was sort of an Irish super-powered version of Jack Wilshere.

It’s worth remembering that he is still discussed in such reverent tones, despite having only had five years of regular first team football for a club that spent much of his time there under-achieving. To put that into modern perspective, he spent less time in the Arsenal first team than Cesc Fabregas, and was only three months older when he left. Yet he is still ranked as the 8th best Arsenal player of all time by an online poll where the majority of voters would have never have seen him play proving Arsenal fans of all ages yearn to soak up as much about the game they love as possible.

Darby’s legacy to the club he loved was significant, discovering the core of the team of ‘nearly men’ of the late 1970s, with schoolboy wonder Liam supported ably by countrymen and fellow Darby finds David O’Leary, Frank Stapleton (the RvP turncoat of his day) and John Devine.

But despite Stapleton’s cup scoring exploits, and O’Leary setting the appearance record for Arsenal Football Club (not to mention scoring the winning penalty in the second round shoot out at Italia ’90), it was undoubtedly Brady that was to become the jewel in the crown for both club and country.

Following a successful trial as 13-year-old in 1969, Liam moved to North London at 15 and it was immediately clear he was a level above his contemporaries in the youth team. It was as early as this that young Liam earned his now infamous nickname, ‘Chippy’, not as some assumed due to his intelligent range of passing, but because of friendly advice from his mum.

“My mother always talked a lot and she told Arsenal’s chief scout that I’d be OK as long as I was given lots of chips, so the chief scout said: ‘We’ll call him Chippy’. In that one second, I was given a nickname which lasted throughout my eight years at Arsenal. Strange. I was never called that in Ireland, or anywhere else.”

Despite him not liking the nickname as he got older, and only the likes of Rice, Jennings and Nelson being allowed to call him by that moniker, you’d be hard pressed to find a Arsenal fan of the right vintage that doesn’t know it!

Less well known is the fact that his Arsenal career was nearly over before it begun. Despite the London professional careers of his elder brothers Pat and Ray (both played for Milwall and QPR), the young Liam initially hated his time as an Arsenal junior, rebelling against the club discipline and refusing to return to the club after Christmas. Even then he was strong minded, “I’d kind of rebelled against the regime, rebelled against the excessive discipline by this one guy.”

It took weeks of gentle persuasion by the Arsenal back-room staff and Irish scouts to convince him to give it another try.

‘The chief scout kept ringing me, wanting me to come back, but he handled it well, never bullying me. After three weeks, I began to miss Arsenal, so I decided to go back. I was never homesick again. Ever.’

By his 17th birthday in 1973 the slightly-built playmaker signed a professional contract with the club. Within a few months, he made his first team debut, coming on for Jeff Blockley in a 1-0 October home win against Birmingham City. Despite a poor showing in his second appearance, a 2-0 defeat to Spurs, manager Bertie Mee was impressed, telling the press “I’m very confident that young Liam Brady will emerge as one of the best midfielders in England over the next few years.”

Later that season, on 30th April 1974, Brady scored his first goal for the club, a trademark strike from 25 yards, in a one-all draw with Q.P.R., a game that was notable for two rather less-than positive reasons. Not only was Brady only on the pitch as a sub because Alan Ball broke his leg (and was never quite the player again), but it was also to be popular goalkeeper Bob Wilson’s last game in an Arsenal shirt. By the end of the season, Brady had racked up 13 first team appearances having only just turned 18.

He was eased into the role of first team starter over the next two years, Brady learned his trade, initially looking to the classy but injury stricken Alan Ball, and made an impression on established first teamers like Eddie Kelly “I would think Liam Brady was the best (I ever played with). I played with him a few times when he was younger and even as a kid he had fantastic ability”

Over time he developed both his physical abilities and tactical awareness to complement his touch and vision, and when first Kelly and then Ball (after leading an attempted dressing room coup, which Brady stood up against) left in 1976 under new manager Terry Neil, Brady found himself as he undisputed master of the Arsenal midfield at the tender age of 20.

It was a role undoubtedly deserved. With the ability to glide past opponents, win tackles cleanly, shoot or pass with minimal back-lift, and cross like an expert winger, he could always keep opponents guessing. It wasn’t just the technical skills and courage he possessed that made him stand out, but the intelligence with which they were applied. His skill demanded that every move passed through him and so he dominated games.

As the centre-piece of Arsenal’s Irish revolution, Brady was key in helping his Northern Irish manager turn around the fortunes of the ailing Arsenal ship, which through ill-judged transfers, ageing stars and unfulfilled youngsters, had been paddling frantically in choppy waters for the three previous seasons. It was definitely the lads from the Emerald Isle that spearheaded the improvement.

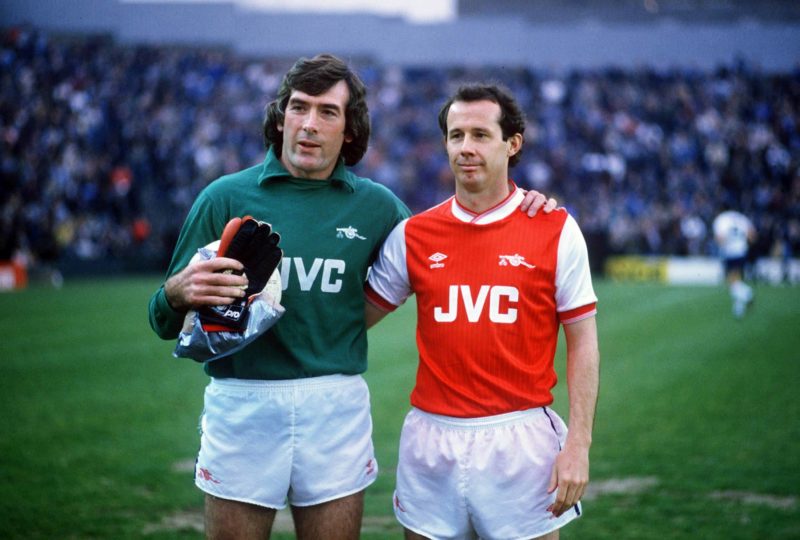

Along with the aforementioned Brady, O’Leary, Stapleton and Neil, there were Northern Irish team-mates, stalwart left-back Sammy Nelson, club captain (and eventual long term coach) Pat Rice and one of the top goal-keepers in the world, Pat Jennings, giving Arsenal a distinctly Gaelic flavour in the age of flares, disco and the winter of discontent. It was Brady’s almost telepathic relationship with Stapleton and his left-sided colleagues Nelson and later Graham Rix (Brady’s best friend at the club), later noted by Marco Tardelli after victory in Turin in 1980, that was the primary component of this developing side.

After two years of consolidation, the maturing core and a couple of astute signings saw Arsenal back in contention for trophies, with Brady the master conductor. A succession of comfortable top third league finishes followed, combined with three consecutive FA Cup finals between 1978 and 1980. Before the first of these Brady was singled out for praise by The Times:

“Victory in the FA Cup Final on May 6th should be the first of many riches heaped upon this superbly creative young team over the next few seasons. Although Rice, the captain, gives them discipline and order, the genius is Brady. He was, as he always is, the most influential player on the field on Saturday. In a match bulging with incident which Arsenal won in a canter by 3-1 against Manchester United. Caressing and manipulating the ball with the left foot, Brady displays the same instinctive sureness and control that nature usually reserves only for single limbed people. Coupled with a vision only the great possess, Brady Is the best midfield player in Britain today. ”

That 1978 final ended in shock defeat to underdogs Ipswich Town, managed by future England boss Bobby Robson. As it happened Ipswich were about to embark on four excellent seasons, culminating in winning the UEFA Cup, but it was still enough of an upset for the scorer of the winning goal, local boy Roger Osbourne, to become faint upon scoring and requite substituting. In fairness, Arsenal’s midfield and frontline were walking wounded, and Brady was sufficiently lacking in fitness to have to be taken off with the lingering effects of ankle injury sustained against Liverpool in the League Cup Semi-Final defeat. He vowed to never to play in a big game when injured again.

The team, and Brady in particular, were determined to make up for it the following year. Following a disappointing UEFA Cup defeat to eventual finalists Red Star Belgrade (another example of the team floundering in a big game with Brady absent – this time suspended after reacting to particularly violent ‘marking’ in the previous round), Arsenal once again made the FA Cup final in 1979. Their opponents, Manchester United, were much fancied having beaten the mighty Liverpool in the semi final.

Brady had other ideas, giving possibly his finest performance in an Arsenal shirt. The Irishman tore Manchester United to pieces at Wembley, with a beautiful ‘pre-assist’ for Brian Talbot’s opener and a signature jinking run and a perfect cross for Frank Stapleton to score a simple headed second. Then, after United hauled themselves level with two late goals, Brady dug deep to launch one final surge into opposition territory. His pass to Graham Rix forced the left winger to accelerate and cross. Alan Sunderland was on the end of it and the rest is history.

Despite that one FA Cup win in the ‘five minute final’ of 1979, the Arsenal team of the late 1970’s probably under-achieved. Looking like a team poised to challenge for major honours in the coming years, Arsenal were hit with two major blows that summer. The first, the forced retirement of potent goalscorer Malcolm ‘SuperMac’ Macdonald, was not a complete shock. The second came out of the blue and is still mourned by Arsenal fans of that vintage today.

Having just been named man of the match in the FA Cup Final and PFA player of the year (the first non UK player to win the award), Liam Brady announced that he would be leaving the club at the end of his contract in 1980.

‘I wanted to be up front with the club and the fans. I’d seen how well Kevin Keegan had done in Germany, so I fancied going there. I’ll admit the money was a big attraction, but it wasn’t the number one reason. I just wanted to live and play football abroad.’

Later he also cited the club’s unwillingness to show ambition lacking his own as reason to leave.

“We had a superb backbone of young talent who would be the core for many years at Highbury. But to win the league we need more depth in the squad. Here was a real chance to push on. The club signed John Hollins but after our cup runs there was enough money in the bank to have signed someone like Bryan Robson and absolutely gone for it. We never did. What I wanted was Terry to sit down with me and discuss his vision of the future, but he never did. I felt like I was being taken for granted. ”

Despite this shock, the determination at the club was to make sure they made the most of the last year of this now world class midfielder. True to this aim, the club competed on all fronts, and but for a frankly farcical fixture list, may well have succeeded.

Challenging for the League, FA Cup and European Cup Winners Cup, the combination of a double legged semi-final victory over Juventus and THREE FA Cup Semi Final Replays against Liverpool, led to 18 high intensity fixtures against top class opposition in six weeks, sometimes with only two days between games. This was in the days of one substitute and very small squads.

The two finals were Arsenal’s 67th and 68th games of the season, and by the time they played 2nd Division West Ham United at Wembley, the team were out on their feet. In a game only remembered for Trevor Brooking’s third ever career headed goal (in nearly 500 games) and Willie Young’s professional foul on 17-year-old Paul Allen, Brady was kept quiet as the Hammers flooded the midfield. It was the greatest cup shock of the last 40 years.

Things were to get even worse four days later in the Cup Winners Cup final, as despite shutting out European giants Valencia and their World Cup winning superstar Mario Kempes, Arsenal lost in a penalty shoot-out, with the normally reliable Brady missing from the spot. It haunted him for a while.

“I’d wake up in a cold sweat thinking about why I didn’t put it in the other corner. People talk to me now about a certain game I played in, or a certain goal I scored, and I’ve no memory of it. But I’ve never forgotten that penalty.”

To add insult to injury, Arsenal immediately had to fly back for an away game at Wolves 48 hours later to keep their European football dreams alive. Remarkably they won 2-1, but lost out away to Middlesbrough on the last day of the season three days later.

So nearly the glorious send off for the finest Arsenal player in two generations, but ultimately fruitless. To add insult to injury, Arsenal only received the maximum £600,000 allowed by UEFA and the EEC for international transfers when Brady went to Juventus. The Old Lady of Italy, having fallen in love with Brady during their Cup Winners Cup semi-final defeat to Arsenal, had gained one of the best midfielders in Europe for a fee that was an insult even by 1980 prices.

Arguably the best player to have ever come through the Arsenal youth system, and certainly the most technically gifted, Brady left to play at the higher level that was Serie A in the 1980’s at the tender age of 24. He racked up 307 first team appearances for Arsenal, scoring 59 goals, and left a whole host of indelible memories.

Probably the most famous is his goal in the 5-0 victory at White Hart Lane on 23 December 1978. Winning the ball in midfield with a firm but skilfully executed tackle on Peter Taylor, Brady took the ball to the edge of the box, before curling it into the opposite top corner with the outside of his left foot. I’m sure there are millions of Arsenal fans who still get shivers at the commentary “…look at that… Oh, look at that!”, as those of my age do at “…its up for grabs now….” or “…its Tony Adams, put through by Steve Bould…”.

Ultimately for Arsenal, the departure of their creative heartbeat and standard bearer left a yawning chasm at the club. Despite a promising third place finish in 1981, the writing was already on the wall with the lack of fluency in the club’s midfield, and things petered into the mediocrity of the mid 1980’s. Essentially the manager had a problem. How do you replace the man who made you tick? Terry Neill never found the answer, and ultimately it cost him his job. Arsenal would not win another trophy until 1987.

“After Brady had gone Arsenal tried out a string of midfielders, some of them were competent, some not, all of them doomed by the fact they weren’t the person they were trying to replace.” – Fever Pitch, Nick Hornby

As for Brady, his Italian adventure was an immediate success despite the weight of expectation. He had been given the legendary Juventus number 10 shirt and, as he later recalled for RTE,

“When the plane landed [in Turin], there was a mass of black and white. [The] Juventus supporters were waiting for me to arrive; it was something I didn’t expect.”

He didn’t disappoint, filling the vital role of trequartista, the team’s primary creator, with aplomb. It was also the way he was off the pitch that made him such a success compared to most players from the UK and Ireland when it comes to settling overseas. His politeness, sportsmanship and willingness to adapt to the Italian way reminded the locals of the legendary John Charles. With his wife, Sarah. he got a flat, decorated it, bought Italian furniture, bought Italian clothes, ate Italian food.

‘It was smashing. I loved everything about Italy.’ He even adapted to their drinking habits after learning from Marco Tardelli among others “that in Italy, they don’t go out drinking for the evening, not the way we do.

But ultimately it comes down to results and he exceeded expectations. Still seen as the architect of the team that won Serie A in both 1981 (where he finished top scorer) and 1982, he also showed his character. Having already been told he was going to replaced by Michel Platini by then Club President Giampiero Boniperti (a consequence of the limits on foreign players and the ego of the rich and powerful), a desperately disappointed Brady was tasked with taking the penalty that would decide the title destination with less than 15 minutes of the season left. Banishing the ghosts of the Heysel penalty miss for Arsenal against Valencia, he sent the keeper the wrong way. As a universally popular player among the fans in Turin, this calm professionalism on the back of the club’s betrayal only served to cement his reputation among the Juventini. He is still viewed with almost as much affection in Turin as in North London. The club still tweets him birthday wishes every year!

Despite improving on his already excellent standards, less collectively successful spells at Sampdoria ‘(‘I played my best football in those two years – and they were very happy.’), Internazionale and Ascoli followed, before he returned to London at the age of 31 to play for West Ham United in 1987. Despite still exhibiting signs of his undoubted class, he couldn’t prevent a poor West Ham from being relegated in 1989, and retired the following summer, scoring from 25 yards in his last game as a professional footballer on 5th May 1990.

Liam Brady also provided invaluable service for the Republic of Ireland National side, and was undoubtedly their star player in an era where the team as a whole were capable of great results, but still wildly inconsistent. He ended up with 72 caps for his country, starting all but two and scored nine goals, his favourite of which was a near post strike from the edge of the box against Brazil in 1987. As well as being expertly taken, it was the only goal in Ireland’s only ever victory against the South Americans. How fitting that the team synonymous with ‘the beautiful game’ were felled by a beautiful goal by a truly beautiful player. Sadly his international career was cut short ahead of the 1990 World Cup finals by a mixture of injury and the mistrust of route one specialist, Jack Charlton. His final international appearance ended with the ignominy of being substituted in the first half of a pre-world cup friendly. Later Charlton admitted he only started Brady in the match to prove to the Irish fans that the great player was past his best and that Andy Townsend was better suited to the team’s style.

“It was disappointing for me. You sense when your time is up or when a manager favours you, or when a manager is supportive of you. It was a sad way to go,” Brady told RTÉ Radio.

Within a year of hanging up his boots, he was installed as Manager of Celtic at just 35, but two years in Glasgow and a further two years in charge of Brighton and Hove Albion disavowed him of any long-term managerial aspirations. Talking about his time at Celtic to Free Kick magazine in 1998, Brady was as honest as ever:

“I’ve got to hold up my hands and say the pressure, without doubt, got to me too. Of course it did. You’ve got to ride the storm and, sadly, I couldn’t manage it. That was why I had to resign.”

It was then that his relationship with Arsenal was re-kindled, when he was hired as Head of Youth Development and Academy Director in 1996, as position he held until the summer of 2014. Under his stewardship, the Arsenal youth team won the Academy league five times and the FA youth cup three, ultimately producing the likes of Ashley Cole, Kieran Gibbs and Jack Wilshere, as well as finalising the development of Wojcech Szczesny, Cesc Fabragas, Nikolas Bendtner and Johan Djourou. Having stepped down to spend more time with his family, Liam remains an ambassador for the club.

As an Arsenal player, Liam Brady left before reaching his peak, less than seven years after his debut as a 17 year old, and only won a single trophy at the club. Despite this, he still gets voted into every Arsenal all-time eleven, and older fans inform me that he was never really replaced until the arrival of Dennis Bergkamp.

It wasn’t just his ability, it was his attitude and the possibilities he represented. He was a truly world class player emerging during a half decade of mediocrity, the youth team kid from a working class family, who on Saturday danced with angels when so many others were floundering in the mud. He was a modern European footballer at a time when much of the English League’s were stuck in the dark ages, and one whose reputation and legend were ensured by leaving when everyone wanted more.

I shall leave the final words to a man who shared many of the highs and lows of Arsenal in the late 70s:

“Liam was a dream to play alongside, because he could deliver a perfect through-ball to you – which is your dream if you’re a striker. Right foot, left foot, and with that brilliant skill he had of making the ball backspin on impact. Like all true greats, he had fantastic balance. He wasn’t blisteringly quick, but he was amazingly smooth to watch. You could give the ball to Liam, and the rest of us could dawdle forward to the opposition penalty area, have a chat, and we knew that the ball would find us.

“Then there was that shot of his,” said Malcolm MacDonald. “The deceptive swerve he was able to put on it was something else. I remember one of his goals at home to Leeds at the start of the 1978–79 season, when he made the ball arc into the net. It was beautiful. Like a lot of Irishmen, he was extremely articulate, who operated with his brains as well as his feet. The thing about Liam was that like any top player, he wanted the biggest prizes. And when success doesn’t come, problems arise.”