When Arsenal won the league at Anfield on 26th May 1989, it was my first high as a football fan and still the greatest 31 years later.

I was the grand age of 11 and this was the culmination of my first season as a real football fan. The final game on the final day, and a live televised football match – then still a rarity compared with today’s 24 hour coverage.

A winner takes it all head to head.

The country’s most successful club and media darlings against the ugly, unloved upstarts from North London in a League Championship shoot out.

A game with real meaning and, for the first time, one that I knew had meaning for me.

Despite the exhilarating energy of a 40,000 plus crowd, my introduction to Arsenal had been couple of drab draws, in meaningless games, while sitting in the relatively sedate east-stand upper tier, and I was only nominally part of the clan. I remained one of the comparatively sane, enjoying the sport for what it was, good play when I saw it, and generally cheering on the underdog.

Luton Town changed that at Wembley in 1988 in the League Cup Final.

My new team, The Arsenal, had been clear favourites after winning it the year before, and were in total control before they snatched defeat from the jaws of victory, complete with Nigel Winterburn inexplicably taking and missing a crucial penalty, and comedy defending that was the start of the end of Gus Caesar’s career.

This was much to the glee of the press and the endless stream of Liverpool fans at a London school in the 1980s, still smarting from Charlie Nicholas’s breaking of the ‘when Ian Rush scores’ spell the year before.

After that loss, I was a real fan, having tasted the pain of defeat and the joy of enemy tribes as a result.

That side was full of good players, though it was not one for the purists. As reliant on work-rate as skill, it had only a handful of players who would trouble the international cap makers.

Unlike today’s superstars, they still seemed within touching distance of us in the stands, and we loved them all the more for it.

For all the assists of Marwood, goals of Smith, brilliance and toughness of Rocky or drive of Tony Adams, my favourites were Lee Dixon and Michael Thomas.

The former made his Arsenal debut in my second game at the ground, an utterly forgettable affair, and Micky T always had a mix of work-rate, smoothness and goal threat, that made me want to play like him.

For the first time I had heroes that weren’t my parents or the remote characters of fiction or stars of screen.

The 88-89 season had been an emotionally turbulent time for me. I had settled into a new school and made friends, my parents had split up with me moving out with my mother, and most importantly I had completed my Panini ‘Football ’89’ sticker album after previous years’ failure.

Against this personal backdrop, Arsenal were greeting my arrival to the ranks with their best league campaign since the early 1970s.

It hadn’t occurred to me that we could win the League until the point we had seemingly thrown it away with awful back-to-back results against Derby County and Wimbledon.

The idea of winning by two clear goals at Anfield in the last game of the season seemed so preposterous, given our form and their invincibility over the previous 15 years, I suspect most fans were, like me, feeling pretty relaxed before the game.

Liverpool hadn’t lost at home by more than a goal in something like five years, and I was just looking forward to seeing my adopted heroes on ITV, whilst being serenaded by Brian Moore.

I watched the whole thing on the sofa with my dad. This was a rare experience now my parents had separated, and I imagine he was more interested in rebuilding his relationship with me than the game, but I was not going to miss this one. In retrospect, my father probably didn’t enjoy the fact that I was so involved.

Arsenal had only become my club after I was taken to the cathedral that was Highbury by my future step-father.

We were talking, or he was trying to, with the football on the TV without too much emotional investment in the unfolding action, when Alan Smith scored the simplest of headers.

The confusion in Brian Moore’s voice, combined with the mass Liverpool protests (mastered long before Fergie’s Manchester United), had me convinced that the goal was not going to count, despite the absence of any infringement. The conversation between referee and linesman seemed to last hours despite the video proof to the contrary.

Suddenly, the game had meaning, and an edge.

The players, fans, commentators and my father and I realised the ridiculous was now possible.

From then until the end it would have taken wild horses to drag pre-teenage me from the screen.

I am sure I wasn’t alone thinking that the first chance for Thomas was the only one we’d get, and his anxious finish almost allowed me to relax.

It was, much as Brian Moore told us, hard luck, well played, and fitting that we should win even if Liverpool won the title. And I felt proud, and not at all disappointed.

Had I been there, I would have sung my squeaky voice raw.

Into injury time. I was absorbing as much of the atmosphere in the ground as possible on a Radio Rentals £5-a-month special before the most extreme emotional moment of my life to that point.

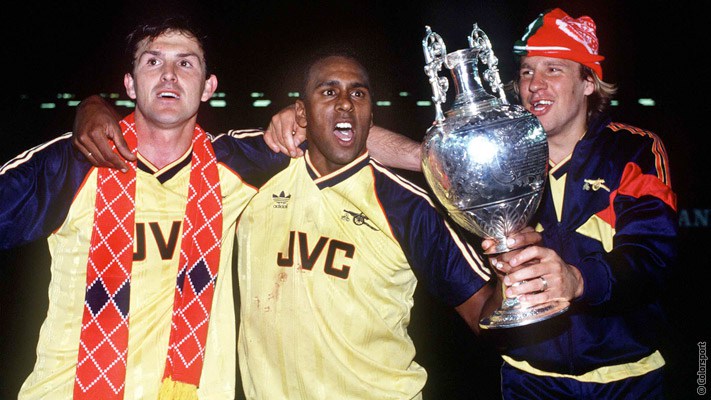

The simplest of goals – ‘up, back and through’ – started by my one favourite and finished by the other, whose calmness as time seemed to stand still as we all watched Steve Nichol and company chasing back.

It was almost zen-like.

I exploded, doing my best to imitate Michael Thomas’s headspin, while my father suggested I “calm down”.

No chance!

The joy was combined with that now familiar football emotion, entirely biased sense of justice.

Liverpool’s Steve McMahon, a talented but spiteful and cynical player who had been kicking and elbowing people unpunished seemingly all season long, had barely finished telling the whole world there was exactly one minute left.

Take that!

My new villain and his friends were vanquished by my relatively new heroes.

Except, of course, the new experience of that feeling of inevitable impending disaster when the home side poured forwards in the remaining minute of injury time.

Then the final whistle went.

The impossible had happened.

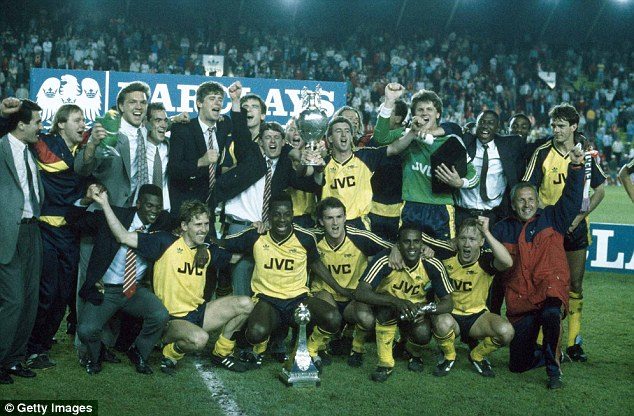

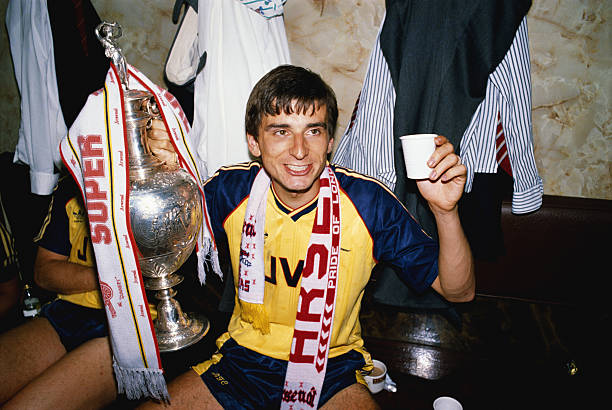

Wild celebrations, incomprehensible pitchside and changing room interviews (the word subtitles only really exists in my mind in Alan Smith’s broad midlands accent) , the sight of O’Leary trying to commiserate with his international team-mates. There was one other very striking memory.

The Liverpool fans staying en masse and applauding when the trophy was presented to Tony Adams. For that I will always have respect for the club and its fans, even if they have had many players down the years that I have found less appealing.

The Arsenal players handing out flowers before the match to commemorate Hillsborough also stuck very strongly in my mind. Both help to remind me that despite the rivalry, these are two clubs that occasionally go beyond the simple tribal boundaries that defines much of professional football.

I still get genuine shivers down my spine and hair standing up on the back of my neck when I hear any of Brian Moore’s commentary from the last 10 minutes of this game.

So much of it is indelibly etched on my brain. My team had done it.

We had won. Against all odds, at the home of our invincible rivals, in the most dramatic way ever. The adrenaline rush was immense, and almost unrepeatable.

Over the next 18 months I saw the release of Mandela and the falls of the Berlin Wall, Ceaușescu and Thatcher, experienced the late 80s dance and indie musical revolution and the way Italia 90 changed the popular consumption of sport at home and across the world.

I was old enough to understand the power of what I was seeing and that they were once in a lifetime experiences, yet till young enough to not fully grasp all the implications.

These were the most formative of my experiences as an observer, and 26th May 1989 was the first.