Popularity among the regulars of the North Bank was never an issue for Sammy Nelson, and there were very rarely calls for him to be ousted from the team, but he never really got the recognition he deserved as a player.

When you stand out so much for your personality, and one moment, in particular, it’s easy to have some of your more practical skills overlooked.

Sammy shares the unusual double of being born on April 1st (1949, in Belfast) and signing for Arsenal on April 1st (1966). Not a bad birthday present!

Like so many of the players who were to come through the ranks and serve the club with distinction in the 1970s, he was brought to Arsenal under the ill-fated tenure of former legendary England Captain Billy Wright, and in his first few months won the FA Youth Cup alongside future full-back partner Pat Rice.

He was at the club for less than three months before the manager was sacked. Happily, for Sammy, new boss Bertie Mee saw enough in the young Ulsterman to retain him in the reserve team, and like many an attacking full-back, this was initially on the left wing.

Despite making his debut in October 1969 (and scoring from distance in the League Cup weeks later), the consistency of first choice full-back Bob McNabb limited him to just six league starts in the following two years, and he only troubled League statisticians four in the glorious double year of 1971. Bizarrely enough, when he featured in the League Cup that season, it was as a makeshift centre-forward. By now however, he had broken into the Northern Ireland international side, where he was to largely remain for over a decade.

It seemed he had cemented his place in the 1971/72 season, when injuries to McNabb allowed him to start over 30 games in all competitions, but McNabb was both more defensively sound and nothing if not a competitor, and the senior man remained primarily first choice until his departure in 1975.

Nelson was very much a full-back in the modern mould, placing rather more onus on his excursions into enemy territory than most of his counterparts in the harum-scarum of the 1970s football League. An excellent crosser, brave (and a little over-zealous at times) in the challenge and blessed with the engine of a marathon runner, Nelson also shared the weakness of many modern full-backs; uncertainty in reading the game and his positioning.

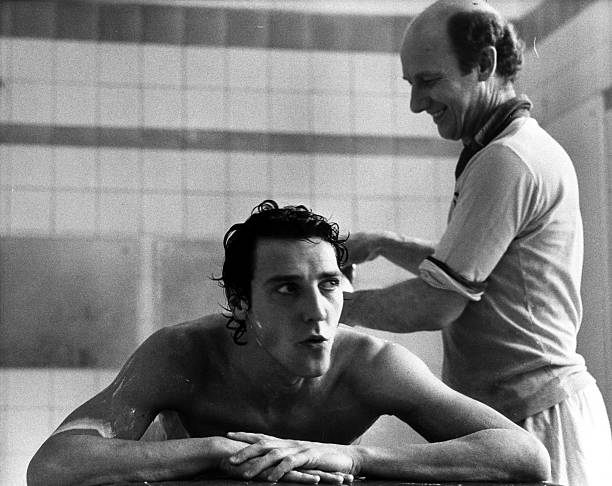

It was a game in which he showed both his attacking prowess and defensive inconsistency that created the iconic photograph for which he is best known. In a home game against Coventry City in 1979, he scored what might be considered an avoidable own goal to give the visitors the lead, and the North Bank was equally generous in letting him know just how they felt about it. Spurred on by professional pride and a certain amount of pique, he took it upon himself to restore parity and did so spectacularly, before reminding the home fans of their earlier jibes by dropping his shorts to moon at them.

Whether retribution or anarchic celebration, the supporters took it in the jovial manner it was intended, his rapport with the crowd long established by then. Typically the Football Association where as cheerless as ever, suspending him for a fortnight.

While this should be just a passing anecdote in a career of longevity at the top level, a well placed photographer ensured that his posterior baring moment was captured for posterity, and probably more fans know about the photo than his career. Indeed, any internet search regarding Sammy Nelson primarily results in stories about the incident or the now iconic photo.

What it did show though, is that Sammy had a fairly unique relationship with the fans. There are endless anecdotes about supporters encountering him and his generosity of spirit, my favourite being the lad who delivered his newspapers that he gave two 1980 Cup Final tickets to.

His warm, engaging personality was not just limited to the fans. He also famously got on with almost all of his team-mates, from both ends of his career, and many of them still consider him a close friend. Almost all cite his infectious character and his endless collection of one-liners.

Like most of the multitudinous Irish contingent at Arsenal in the 70s, Sammy enjoyed his best form for the club at the end of the decade, enjoying a particularly successful left-sided triumvirate with the emerging Graham Rix and the young genius, Liam Brady. Neslon and the team (apart from the long-serving Pat Rice and David O’Leary) collected their only trophy with the club in the second of the three consecutive FA Cup final appearances in 1978,1979 and 1980, after the ‘five minute final’ against Manchester United. Most forget that he started the move for Alan Sunderland’s late winner.

His final really big game for the club was to come a year later, in the European Cup-Winners’ Cup final in 1980. An Arsenal side exhausted by over 60 fixtures that season and 10 games in a month, having lost the FA Cup final just days before, became the first to lose a major final in a penalty shoot-out. As the shoot-out went into sudden death, he found himself uncharacteristically nervous.

“Pat Rice and I were in the centre-circle discussing who would go next. I said, ‘Go on, take some responsibility.’ Pat replied: ‘No. It’s you next.’ But as he said it Rix missed, so we didn’t need to decide.”

That summer, the younger and, in all honesty, better Kenny Sansom arrived from Crystal Palace, and as was fitting for England’s first choice left-back at just 21, he walked straight into the side. The writing was on the wall for Nelson, and the following year, after a year almost exclusively out of the side, Sammy knew it was time to move on. He took his sweet left foot and endless selection of corny jokes to Brighton for a fee of £40,000, which was fair enough for a full-back at 32 and in decline.

After 15 years at the club, over half of which serving as second choice, he had racked up 338 League appearances and 12 goals.

He spent 2 years on the south coast, losing in the fourth FA Cup final of his career (in a replay against Manchester United) and in the summer of 1983 he decided to hang up his boots. That game at Wembley was to be his last.

After leaving Arsenal he passed a half-century of appearances for his country at the 1982 World Cup in Spain, where Northern Ireland suffered at the hands of the same bizarre qualifying system that saw England eliminated despite topping their group and remaining undefeated.

He briefly worked as a coach at Brighton, before selling life assurance and pensions from offices on the Charing Cross road, commuting by train from his home in Hove. In more recent years, he has also spent time on the Legends Tour at the Emirates. His daughter Emily is married to recent England cricketer Matt Prior.

Always intelligent and by now famous for his sense of humour, he has quite often attended AISA events as a guest speaker, and has certainly lived up to his reputation.

He is also a dyed in the wool Gooner.

‘Even after all this time I desperately want Arsenal to win. When I watch them on television I get so tense I sometimes have to leave the room.’

It is not unusual for a person to be largely publicly defined in microcosm. For a moment, story or photograph to surpass their wider self in terms of the perception of those who don’t know them. This is particularly the case in sport. But for most, this captures triumph or disaster, elation or misery, or at least a moment of high drama.

In Sammy Nelson’s case, a photograph of a moment of levity has somehow supplanted his career in the wider consciousness. Unless you are an Arsenal or Northern Ireland supporter of a certain vintage, you are far more likely to know a grainy black and white image of him displaying his underwear to a jubilant North Bank than the details of his career.

For a player of his thrust, enthusiasm, loyalty, longevity and success at the highest level, it seems a terrible shame that his achievements and talent are so often overlooked, not to mention the approach and style of play some way ahead of its time in domestic football.

But on the flip side of the coin, much of his enduring popularity was as a consequence of his personality. And there is probably no other footballer of his Arsenal vintage quite as likely to see the funny side.