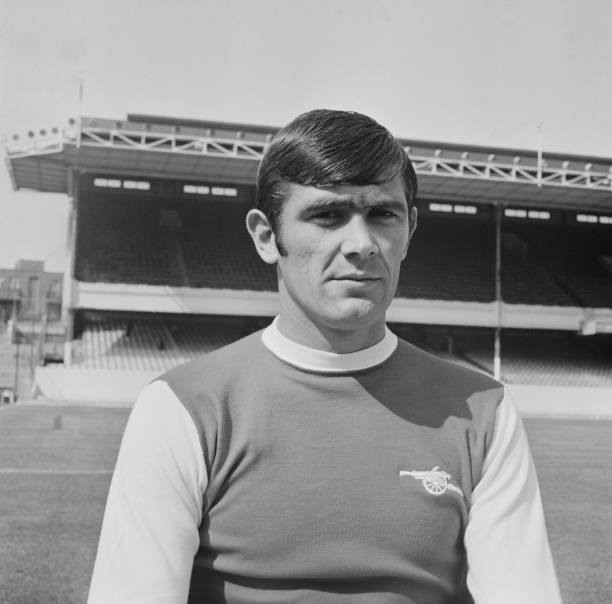

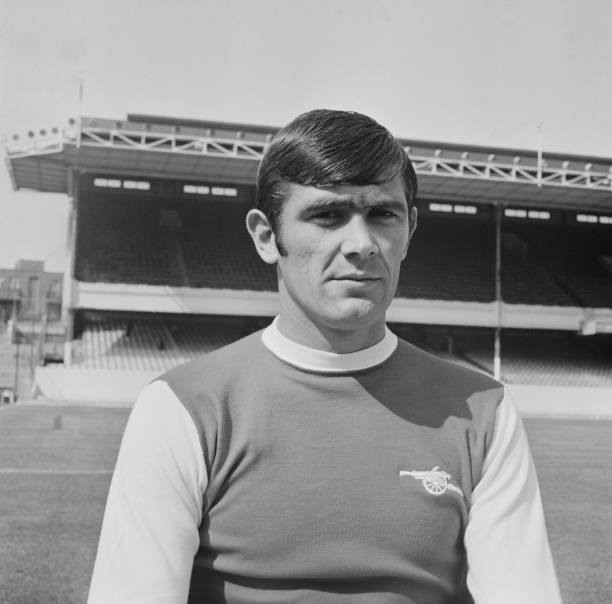

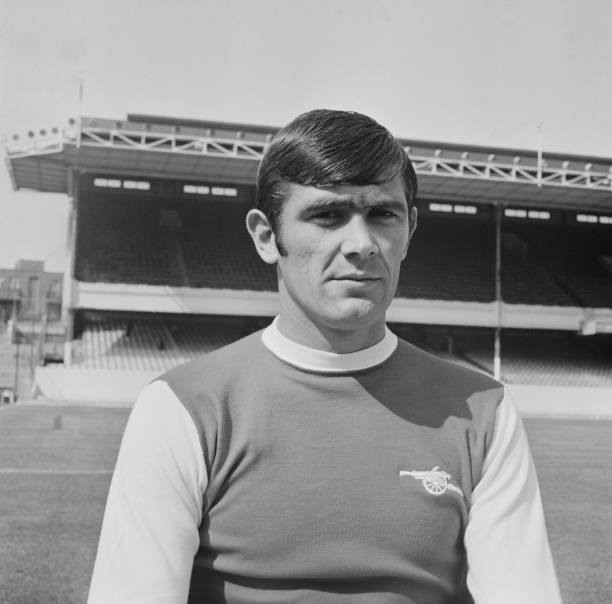

Some players come into the category of the under-appreciated because they are over-shadowed by superior team-mates. Others because they excel in under-achieving teams. There are even those whose ebullient personalities serve to distract from their dedication and skill. None of these apply to Peter Frederick Simpson.

One of the most consistent and accomplished central defenders of his generation, Peter Simpson was lauded by the Highbury faithful, but consistently overlooked elsewhere.

Despite over 450 appearances in the top flight over a 15 year period, as well as being a winner of domestic and European silverware, he wasn’t selected to represent his country even once.

In an age where pretty much only Bobby Moore was allowed exemption from the prevailing English model of the abrasive, long-ball playing stopper, it was repeatedly deemed that there was only room for one ball-playing defender in the team, and that was always going to be England’s world cup winning skipper. What seemed harder to understand was why, although he made the preliminary England squad for the 1970 World Cup, he was cut from the final 22, with the deteriorating veteran Jack Charlton given preference.

Many attributed his lack of recognition to a diffident personality that resulted in him eschewing headlines and appearing to hide his light under a bushel. His lack of public confidence and laid back passivity off the pitch may have counted against him. It certainly contributed to his nickname, ‘Stan’, after the easy-going half of Laurel and Hardy, and it has been said that he needed gee-ing up by manager and team-mates in the early part of his career. Another player with the same ability, but greater intensity may well have been more widely appreciated.

Perhaps some of his quiet, unassuming nature could be attributed to his childhood. Born and raised in the tiny Norfolk seaside town of Gorleston-on-sea (now part of Great Yarmouth), he didn’t have a lot of contact with the wider world until his footballing prowess started to shine through.

Simpson initially joined Arsenal as a member of the club’s groundstaff in 1960 (clubs were not allowed to sign youngsters as players immediately after they left school at 15, although of course, the boys could work), before signing as an apprentice a year later in October 1961, at the age of 16. By the following May, he had turned professional, though it would be nearly two more years before his first team debut at home to Chelsea in March 1964.

It was an inauspicious start. The man he was nominally marking, Bobby Tambling, scored all four goals in a 4-2 win for the visitors. This confirmed the fact that he wasn’t quite ready for First Division football, and he made only 22 more appearances over the next two and a half years. However, at the beginning of the 1966-67 season, Bertie Mee took over as manager and made Simpson a first-team regular, a state of affairs that was to continue for the most of the following 11 seasons.

His Arsenal career started out with him something of a utility squad member, playing in virtually every outfield position, but by 1967 he established himself as a regular in the newly adopted back four, alternating between central defence and either full-back position as required. Within a year, he had become undisputed first choice at centre-half, generally alongside either of the solid but not totally convincing options of Terry Neil, Ian Ure and later John Roberts.

Team success, however, didn’t follow immediately. 1968 and 1969 saw Arsenal lose successive League Cup finals, to favourites Leeds United and massive underdogs Swindon Town respectively. These two underwhelming league campaigns were followed by a third in 1969-70, and in March, with Arsenal languishing in mid-table, and out of both domestic cups, the success of the next 15 months seemed a million miles away. But then a combination of an injury crisis and the ingenuity of Don Howe intervened, and Frank McLintock was moved from his position of left-half (sort of box-to-box) to central defence alongside Simpson. The shift, though reluctantly entered into by McLintock, by now 30 and a midfielder all his career, was to work almost instantly, and galvanise the team. Simpson seemed to flourish further, perhaps energised by the intensity and boundless enthusiasm of his new partner. And apparently captain Frank was very good at giving the almost shy Simpson the constant reassurance in his ability that the younger man needed to flourish.

As a pair that spring they provided the solidity to help the progress in the Fairs Cup (Later the UEFA Cup and now the Europa League). McLintock’s first game as first choice centre-half saw them defeat Dinamo Bacau 2-0 away in the Quarter Finals, eventually winning 9-1 on aggregate.

The Semi-Final saw Arsenal despatch Ajax 3-1 over the two games, due to a Charlie George brace and brilliant defensive displays in both legs. To put it into context, this was the great Ajax team of Cryuff, Krol, Haan, Neeskens, Muhren and Keizer that were runners-up in the European Cup the previous season, runaway domestic title winners (for the 4th time in 5 years), and were to provide the core of the Holland team that thrilled the world throughout the 1970s. Oh, and they won the next three European Cups in a row with almost exactly the same squad, the second of which included revenge of Arsenal en route, via a dodgy penalty in Amsterdam.

In the final, Arsenal faced Anderlecht. The classy Belgians were enjoying a good run and were favourites against Bertie Mee’s side whose domestic form remained unconvincing. Their patient build-up beffuddled the Arsenal team used to a much higher tempo, and they took a 3-0 lead in Brussels. The crucial moment, though, was when 18-year-old Ray Kennedy came off the bench to score with his first touch. That foothold and McLintock’s now legendary ‘up and at-em’ dressing room speech, were to prove vital for the home leg.

In front of a packed house, with thousands more outside, Arsenal piled wave upon wave of pressure on their visitors, and goals from first Kelly and then Radford brought the tie level on aggregate, and with Arsenal winning on away goals, before Jon Sammels sealed a famous victory late on.

With parallels to the glorious night at Anfield 19 years later, Arsenal needed to score at least twice and not concede, and this victory was built as much on a brilliant performance by the defence as the goalscoring prowess of those at the other end.

Simpson and McLintock had played alongside each other for a little over 6 weeks, and now they had marshalled the back-line for the club’s first European trophy win. And the skipper had won his first final at the fifth attempt.

“On the night, as a team, we couldn’t have played any better. Everyone was on fire and the crowd was really behind us. Winning that cup was so important to me and the club. The first trophy in 17 years. We were becoming a good team and now we had the confidence to go with it.”

It certainly was to be catalytic for all involved. Directly after the game, Bertie Mee said to the press “The experience we gained tonight will be invaluable for winning our next objective – the Football League.”

As we all know, the ex-army medical corps sergeant turned club physio, turned surprise manager, succeeded in that objective the very next season, alongside the FA Cup to be only the second club to achieve that double feat in the 20th Century.

Simpson actually missed the first three months of glorious campaign following a cartilage operation, and although John Roberts proved an able deputy, Simpson came straight back into the side when fit and was ever present from there on in.

Arsenal’s first credible title challenge in 18 years ended in triumph with a final day win at White Hart Lane, and the FA Cup was added five days later. However, as for many of that history-making team, that was as good as it got for Peter Simpson, despite near misses in the next two seasons.

Another Wembley disappointment came in 1972, as the FA Cup final ended in a 1-0 defeat to Leeds, and in 1973 Arsenal were FA Cup up semi-finalists and League runners-up, three points behind Liverpool, having led for parts of the season.

Simpson was now at his peak as far as his personal form went, though he was starting to pick up a few more injuries. However, as 1972 turned into 1973, seeds were sewn that would undermine the future of the defensive partnership that had been so effective since 1970, and ultimately that of the team’s fortunes.

McLintock was dropped in favour of the clearly inferior Jeff Blockley, and reacted badly, rowing with the Manager. Mee, whose military past informed his approach, made it clear that his insubordination would not be tolerated, and by the summer Arsenal’s inspirational captain was shipped off to QPR for a mere £25,000. This went down badly in the dressing room, and particularly with Simpson, who missed the confidence, reassurance and forceful personality of his partner in greatness, and was saddled with a succession of mediocre centre-halves for to try to work with.

From then on, the downward trajectory of Bertie Mee’s side accelerated. As injuries, age and unfulfilled promise slowly dismantled Arsenal’s collection of double-winning heroes, Simpson was one of the few to bridge the gap between 1971 and the Irish infused cup specialists of the late 1970s.

Though never quite the same without the presence of McLintock beside him, and with injuries affecting his mobility and position as undisputed first choice, Simpson remained at the club until 1978. Having lost his place in the team in the relegation-threatened 1975/76 season, he enjoyed a resurgence in 76/77 alongside the man who had appeared to have replaced him, the stylistically similar David O’Leary.

By the second half of the 1977/78 season Simpson found himself on the outside looking in due to the arrival of Willie Young, despite the team only conceding in two of the 9 games he featured in that year. While there was no doubt his powers had diminished somewhat, he suffered more from the fact that Young was a better compliment for the now fully established O’Leary, in the same way that McLintock had been for Simpson himself almost eight years previously. He left at the season’s end.

Upon his release from Arsenal, he didn’t fancy playing for another English top-flight side, and instead enjoyed a year in the North American Soccer League for the New England Tea Men, having enjoyed offseason loan spells with the short-lived Toronto Falcons and Boston Beacons in the late 1960s. He later found himself playing a little at non-league level, before managing a Haulage company. He now lives a quiet life back in Great Yarmouth, avoiding interviews even more successfully than he did at the time.

In all he had played 477 times for the club, scoring 15 goals, in the fifteen years since his debut, making him tenth on the club’s all-time list of appearance makers.

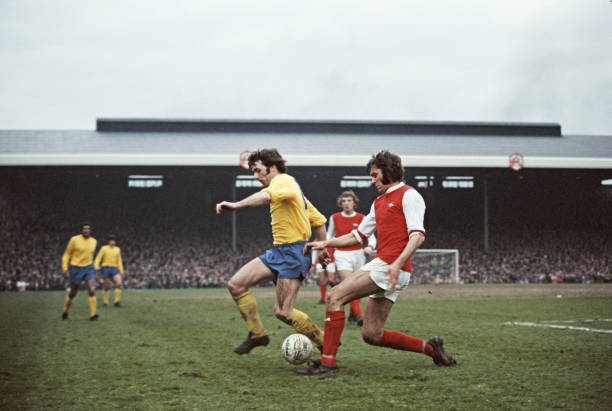

Peter Simpson was a defender very much of the modern ilk at a time when footballing dinosaurs roamed much of the First Division. Though strong in the air and an expert last-ditch slide tackler, he preferred well-timed interceptions, positional soundness and calm distribution to the blood and thunder, hoof-and-hope approach of many of his contemporaries. His passing ability was definitely unusually developed for a defender of that era, and he was equally comfortable playing slick interchanges with his midfielders or playing long left-footed balls crossfield to the opposing winger. He was tough as old boots, too, frequently ‘wearing’ the deliberate elbows of the likes of Joe Jordan. Numerous observers of the time have since commented that Arsene Wenger would absolutely love to have a player of his ilk at his disposal.

All this was recognised and appreciated by those who saw him on a weekly basis in North London, but somehow he barely made a ripple on the wider stage. Perhaps it was the misfortune of his peak coinciding with that of Bobby Moore and Norman Hunter. Perhaps it was the unfashionable nature of an almost universally underrated side that counted against him, with ex-Spurs man Alf Ramsey seemingly determined to avoid selecting anyone who played for Arsenal.

Or perhaps it was because he was a modest, quiet man, who’d prefer a silent fag at half-time to the ranting and raving of others, and who never courted publicity, and most importantly, wasn’t that interested in football, beyond his teammates and his club. He also crucially lacked that element of bravado and self-confidence that captures the imagination of the casual observer, and the absence of any relationship with the press meant that no-one bar his team-mates were blowing his trumpet for him.

Maybe he just never got the external accolades he deserved because he just wasn’t interested in receiving them.