Arsenal managers

Arsene Wenger was at Arsenal for 20 years but before him, we had numerous other managers – though not as many as Spurs!

Not including interim and caretaker managers, Arsenal have had 21 bosses since we formed in 1886.

Wenger was with us the longest and was in charge of the most games (1235), while William Elcoat was in charge of the fewest (44).

Wenger also has the best win percentage, around 57%, out of all the managers not including the interim bosses who were only in charge for a handful of games.

The worst win rate was George Morrell, who only won around 37% of the 309 matches he was in charge of.

Mikel Arteta is the current manager of Arsenal Football Club.

Arsenal’s first manager is often cited as being Thomas Mitchell but there is a case to be made that Sam Hollis did the job before him.

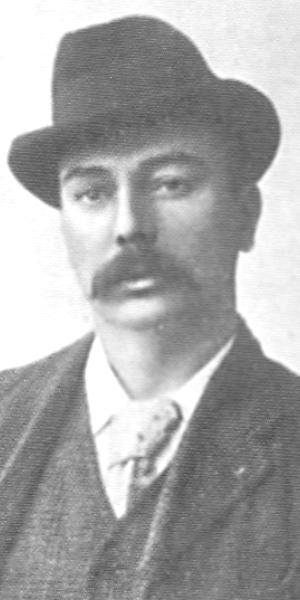

Sam Hollis (1894-1897)

As Untold Arsenal note, there is some debate as the role Sam Hollis played at Arsenal and if he was the club’s first manager. Arsenal.com say he is, so on that basis he’s included here but that piece by the Untold team linked above is worth a read.

Born Sam Woodroffe Moore, Hollis hailed from Nottingham where he was born in 1866 to an unmarried mother, changing his name to Hollis when his mother married Edward Hollis in 1868.

A Freemason from 1905, Hollis was appointed ‘secretary-manager’ in 1894 according to the official website and ‘the first individual to be placed in charge of team affairs.’ The team had been managed by committee before that.

Hollis left the club in the Spring of 1897 for Bristol City where it was said in the press at the time that he ‘will blossom forth as a manager, and many will regret his going. Always a conscientious worker for his employers, he will be sadly missed and although some may possibly differ with him in some of is methods, yet few will wish him anything but the best of luck.

Thomas Mitchell (1897-1898)

Thomas Brown Mitchell is considered by some to be Arsenal’s first professional manager, appointed in March 1897 after a distinguished spell at Blackburn Rovers where he twice won the FA Cup. Born in Dumfries, Scotland around 1843, Mitchell entered football management in an era when “secretary-manager” roles placed him in charge of both team affairs and boardroom duties, long before such jobs were clearly separated. Arsenal recruited him not only for his pedigree, he had managed and helped build one of England’s top clubs, but also as a statement of new ambition after a disappointing FA Cup defeat to Millwall.

Mitchell’s reputation at the time was substantial. At Blackburn he had overseen back-to-back FA Cup victories in 1890 and 1891 and was known for his strong opinions about player training and discipline, which ultimately led to his departure from Rovers after a disagreement with the board about footballing practices. Arsenal acted quickly, offering him what was considered a very lucrative deal of £200 per year, making him one of the highest-paid managers in England.

His tenure at Arsenal lasted less than a year. Although he improved the club’s fortunes on the pitch, taking them from 10th to 5th in the Second Division in the 1897-98 season, and was responsible for a number of signings, neither Mitchell nor most of his recruits stayed for long. He resigned on 10 March 1898, reportedly due to frustration with club management and the challenges of effecting change in a short time. After leaving Arsenal, he returned to Blackburn Rovers.

Mitchell’s legacy, though brief, is significant: he was a pioneer, introducing professional managerial standards and laying the groundwork for Arsenal’s evolution from a works team to a modern, ambitious football club. He died in Blackburn in 1921, but remains an important figure in Arsenal’s early history, and one of the game’s early tactical thinkers.

William Elcoat (1898-1899)

William Elcoat took charge in April 1898 following the resignation of Thomas Mitchell. Born in Stockton-on-Tees in 1859, Elcoat had built his reputation with Stockton FC, where he oversaw a successful side and was known for his organisational skills, sharp eye for players, and no-nonsense approach to discipline. Arsenal, then playing as Woolwich Arsenal in the Second Division, saw in him someone capable of building on Mitchell’s foundations and moving the club closer to promotion.

Elcoat’s time in charge lasted just under a year. He was active in the transfer market, bringing in a significant number of players, mainly from the North-East of England, and placing an emphasis on athleticism and hard work. His recruitment strategy meant a rapid turnover in personnel, which gave the squad an unsettled feel, but also raised the general standard compared to what he had inherited. On the pitch, Arsenal finished the 1898–99 season in 7th place, an improvement on earlier campaigns, suggesting the team were becoming more competitive.

Despite this progress, Elcoat resigned in early 1899 after disagreements with the board over the level of control he should have in football matters, particularly around signings and team selection. The split was abrupt and he returned to the North-East, stepping away from the professional game before the turn of the century.

Although his tenure was short, Elcoat’s methods reflected the transitional nature of football management at the time, when the role was evolving from that of a club secretary with incidental control over the team to a fully empowered manager. His willingness to scour the country for talent and upgrade the squad left a mark, even if his departure meant others would carry the work forward.

Harry Bradshaw (1899 – 1904)

Harry Bradshaw was appointed in the summer of 1899 and served until 1904, making him the club’s first long-term and truly successful figure in the role. Born in Burnley in 1853, Bradshaw arrived at Arsenal after managing Burnley, where he had guided them to the club’s best league finish then achieved and earned a reputation for tactical innovation, particularly for introducing a “Scottish-inspired” passing game built around team movement and short passing.

At Arsenal, Bradshaw transformed the club both in the dressing room and on the pitch. He built an almost entirely new squad, overseeing the recruitment of influential players like Archie Cross, Percy Sands, Jimmy Jackson, and Jimmy Ashcroft. Bradshaw’s focus on a more fluid, technically skilled style of football moved Arsenal away from the direct, physical approach that had dominated English football, marking a key development in the club’s identity.

During his five seasons in charge, Bradshaw established Arsenal as promotion candidates in the Second Division. After several close calls, the club achieved its long-sought goal in the 1903–04 season, finishing second and being promoted to the First Division for the first time in Arsenal’s history. Remarkably, 18 of the 20 players in that squad were entirely Bradshaw’s recruits. He also delivered some of the club’s first big results, including record victories and cup runs that established Arsenal as a competitive force.

Bradshaw’s tenure ended in the summer of 1904 before he could manage Arsenal in the top flight. He left to become Fulham’s first professional manager, tempted by both the club’s ambition and a generous pay package. At Fulham, he quickly added to his credentials by winning back-to-back Southern League titles and leading them into the Football League.

Bradshaw is remembered as the architect of Arsenal’s first era of real progress, laying many of the foundations for the modern club: a focus on tactical sophistication, ambitious recruitment, and an attacking, team-based playing style. His legacy includes not just his wins and promotions but the shift in footballing culture he brought to north London.

Phil Kelso (1904 – 08)

Phil Kelso managed Arsenal from 1904 to 1908, guiding the club through its first transformative years as a First Division team and leaving a significant imprint on its early identity. Born in Largs, Scotland, in 1871, Kelso came to Arsenal after a spell at Hibernian. He was appointed shortly after Arsenal’s historic promotion in 1904, taking over from Harry Bradshaw at a time when the club was just beginning to establish itself among England’s elite.

Kelso was a strict innovator, one of the first at Arsenal to impose a genuine sense of professionalism. He insisted that players live locally, forbade smoking and drinking, and introduced the then-revolutionary practice of assembling the team a day or more before matches to prepare collectively. This approach laid important groundwork for the standards later brought by figures like Herbert Chapman.

On the pitch, Kelso achieved successes no Arsenal manager had managed before. He led Arsenal to their first two FA Cup semi-finals, in 1906 and 1907, and for the first time took the club to the top of the First Division table, if briefly, in October 1906. His best league finish was seventh in 1906–07 – impressive given Arsenal’s inexperience at this level and limited financial power, especially compared to established rivals.

Kelso’s four seasons saw league placings of 10th, 12th, 7th, and 14th, but these must be viewed in context: keeping newly promoted Arsenal in the First Division was itself a noteworthy accomplishment, and the squad’s lack of resources made genuine title challenges unrealistic. He also played a key role in breaking Arsenal’s cycle of early FA Cup exits, bringing much-needed prestige and attention to a club then viewed as peripheral by many in the game.

However, mounting financial difficulties at Arsenal and the stress of managing under such constraints led Kelso to resign partway through the 1907–08 season. He returned to Scotland, reportedly to run a hotel, before being tempted back to London in 1909 to manage Fulham, where he would become their longest-serving manager.

Off the field, Kelso’s legacy endured: he set standards of discipline, organisation, and professionalism that changed Arsenal’s trajectory, paving the way for future growth. He died in London in 1935.

George Morrell (1908 – 15)

George Morrell managed Arsenal from 1908 to 1915, presiding over a difficult and precarious period marked by financial struggle and uncertainty about the club’s long-term future. Born in 1872 in Kilmarnock, Scotland, Morrell had enjoyed success with Morton before arriving at Woolwich Arsenal, as Phil Kelso stepped down amidst growing off-field turbulence.

Morrell inherited a club low on resources. Arsenal’s finances were fragile, and with the team often languishing in the lower reaches of the First Division, they were forced to sell leading players simply to stay afloat. Under these constraints, Morrell focused on keeping the club in the division, generally fielding sides composed of bargain signings and youth products. Despite losing talents like Tim Coleman and Bert Freeman, Morrell masterminded a remarkable escape from relegation in 1912–13, a season that also saw Arsenal record the lowest league attendance in history – just 1,554 spectators for a match against Bury.

Perhaps most significantly, Morrell was manager during Arsenal’s dramatic move from Woolwich to Highbury in the summer of 1913, a controversial relocation intended to guarantee the club’s survival. Although they were relegated to the Second Division that same year, the move to North London laid the groundwork for Arsenal’s future transformation into one of English football’s giants.

On the pitch, Morrell’s seven seasons produced modest results: five years in the top flight, then promotion contenders in the Second Division before competitive football was halted by World War I. Arsenal missed out on promotion under Morrell by two points in the final pre-war season.

As the war took its toll and competitive football was suspended, Morrell resigned ahead of being sacked in 1915 and returned to Scotland, going on to manage Third Lanark.

His Arsenal tenure was defined by firefighting and survival, rather than silverware or style, but he steered the club through its greatest existential crisis. Without his stewardship during the move to Highbury and through years of near-bankruptcy, Arsenal’s later ascendancy would simply not have been possible.

Leslie Knighton (1919 – 25)

Leslie Knighton was Arsenal’s manager from 1919 to 1925, appointed as the club’s first post-war manager after competitive football resumed following World War I. Born in 1887 in Derbyshire, Knighton had previously coached at Huddersfield Town, Manchester City and Leeds City before joining Arsenal, where he came highly regarded for his innovative training methods and eye for emerging talent.

Knighton inherited a club eager to establish itself as a serious First Division contender after years of instability and financial rescue by new chairman Sir Henry Norris. Despite some ambition, Knighton worked under tight restrictions: Norris imposed strict limits on transfers, wages, and even player size (famously insisting Knighton not sign anyone under 5’8″ or over 11 stone), believing this would avoid attracting expensive “stars”. Knighton often resorted to creative and sometimes desperate signings, including players from non-league, Scotland, and even, on one occasion, using a “mystery” goalkeeper wearing a cap pulled low to mask his identity.

Results under Knighton were inconsistent but, at times, promising. Arsenal frequently finished mid-table, with best league results of ninth place in 1920–21 and an FA Cup semi-final in 1922 against Preston, the club’s first significant cup run since moving to Highbury. He gave debuts to a number of players who would later become club stalwarts, including Alf Baker and Bob John.

Knighton’s Arsenal tenure, however, was marked by frustration. His ambitions were repeatedly thwarted by Norris’s interference, culminating in disputes over signings and team selection. After a disappointing 20th-place finish in 1924–25, and shortly after Herbert Chapman became available, Knighton was dismissed in May 1925. He later claimed Arsenal’s failures were down to Norris’s parsimony, publishing outspoken memoirs that gave a vivid, sometimes controversial account of life at the club.

After leaving Arsenal, Knighton managed Bournemouth and Birmingham City, enjoying greater success and leading Birmingham to the 1931 FA Cup final. He died in 1959, remembered as a resourceful and resilient figure who steered Arsenal through the turbulent years between the wars, and whose struggles set the stage for the transformation brought by Chapman.

Herbert Chapman (1925 – 34)

Herbert Chapman is an Arsenal legend, but shouldn’t he be a footballing one all fans know?

The legendary Arsenal manager, revered by Arsenal fans everywhere, is rarely mentioned when it comes to discussions about those who changed the wider game or had a massive impact, when that conversation involves people not connected with or to Arsenal.

Everyone knows the name Bill Shankly, for what he did at Liverpool or Matt Busby, with Manchester United, but Herbert Chapman? Mention him and many still scratch their heads.

He did more to help develop the game than either of those two.

Perhaps it’s a matter of time, although I first wrote this in 2015, updating it now to say not much has changed.

Chapman was a manager long before most of us were alive, perhaps that plays a part. He had come and gone before those better-known greats did their thing.

Taking over at Arsenal in 1925, Chapman managed the club until his death from pneumonia in 1934, when he was still only 55.

His Arsenal salary of £2,000-a-year was said to be the highest ever paid in football, and it was one Chapman repaid many times over, the club turning a gross profit of £15,000 for the three seasons he was there as he guided Arsenal to back-to-back league titles.

Chapman did the same with Huddersfield Town while he also guided both sides to FA Cup success.

Unlike his heralded United and Liverpool counterparts Chapman didn’t, however, win a European trophy, but that was because UEFA did not come in to existence until 20 years after his death. You can’t win what doesn’t exist.

While Shankly and Busby might have lifted the fabled European cup, it was Chapman who actually proposed the concept of a European-wide competition in the first place, shortly before his sudden death.

A big fan of the European game at a time when it was not fashionable to be one, Chapman also saw past race, nationality and everything else that held sway in the game at the time, becoming one of the first to even consider signing black players or ones from abroad.

One of the first modern pioneers of the game, Chapman’s innovations changed the shape of football in the 20th century; from the introduction of his famous WM formation, installing floodlights at Highbury (even though they were not allowed to be used for games until the 50’s), putting numbers on the back of shirts, using physiotherapists and masseurs and overhauling training methods, playing with white balls, and changing Gillespie Road tube station to Arsenal.

Herbert Chapman was not afraid to experiment in order to find an edge for his team and many of his methods live on today, albeit in a more modernised form.

And that’s only a sample of what he came up with.

The son of a coal miner, Chapman’s playing career was unremarkable, but the mark he left on the game as a manager still runs throughout it today like the Thames through London.

Who knows what else Chapman might have dreamed up had he not died preparing Arsenal for their third league title in a row.

Chapman, Busby and Shankly all won two FA Cups. The United manger five titles, the Liverpool one three and slap bang in the middle was Chapman with four.

It might be 143 years since the great man was born, but that’s no reason to forget his name.

Chapman deserves, at the very least, to be mentioned in the same breath as those others who so many hold in high regard.

Herbert Chapman’s funeral

Newspaper report from the Hartlepool Daily Mail, Wednesday, 10 January 1934

“HERBERT CHAPMAN BURIED CHURCHYARD A GARDEN OF BLOOMS

“The churchyard at Hendon was transformed into a garden of rare blooms today, when Mr. Herbert Chapman, manager of the Arsenal Football Club, was buried.

“The sombre yews, the bare trees, the grass plots, the flower beds – all were covered with flowers in wreaths, crosses, chaplets, and sheaths. Through them walked every one of the Arsenal players and leading sportsmen from all parts of the British Isles. The red and white the famous club was splashed everywhere.

“Among the flowers on the coach which preceded the hearse was floral set of goalposts and a ball.

“Six members of the Arsenal start acted as bearers, and, in addition to the leading football clubs and sporting organizations in this country, the Sporting Club France, the Swedish and Danish and Austrian clubs showed that they too deeply regretted the passing of great manager.”

Joe Shaw (1934)

Joe Shaw was a central figure in Arsenal’s early history, dedicating nearly five decades to the club as player, captain, coach, and manager. Born in Bury, Lancashire, in 1883, Shaw joined Woolwich Arsenal from Accrington Stanley in 1907 and soon became first-choice left-back, later moving to right-back after the First World War. Widely respected for his consistency and leadership, he made 326 first-class appearances for Arsenal but never scored a goal.

Shaw captained Arsenal after the club’s return to the First Division in 1919 and was only the third player to reach 300 appearances for the club at that time. His playing days encompassed major moments in Arsenal history, from their relegation and move to Highbury to the early years of rebuilding in north London.

On retiring from playing in 1922, Shaw became manager of Arsenal’s reserve side, building a reputation as a mentor who won nine championships with the second string over twelve seasons. His most famous contribution to the club came in January 1934, when legendary manager Herbert Chapman died unexpectedly. Shaw stepped up as caretaker manager for the remainder of the 1933–34 season, steering Arsenal to the First Division title and ensuring Chapman’s work was not wasted. In this brief stint in charge, Shaw recorded the highest win percentage of any Arsenal manager who oversaw more than 20 matches.

After George Allison’s appointment, Shaw returned contentedly to his role in charge of the reserves and later served as assistant manager to Tom Whittaker after the Second World War. He even had a brief spell as a coach at Chelsea, before finally retiring in 1956, having served Arsenal for 49 years. Shaw died in September 1963, aged 80, and is remembered as a loyal servant whose devotion and achievements deserve greater recognition

George Allison (1934-1947)

George Allison was Arsenal’s manager from 1934 to 1947, guiding the club through both a golden era and the immense challenges of the Second World War. Born in County Durham in 1883, Allison was originally a journalist and broadcaster rather than a professional footballer. He became closely involved with Arsenal from the 1910s, first as the club’s programme editor and later as club secretary, building a deep understanding of both its sporting and commercial operations.

When legendary manager Herbert Chapman died suddenly in January 1934, Allison was promoted from the boardroom to the dugout, initially on a temporary basis. Arsenal were already a formidable force thanks to Chapman’s work, and Allison’s appointment ensured stability. In his first months, he led the team to the First Division title in 1933–34, securing a third consecutive league championship for the club. He retained much of Chapman’s tactical framework but proved a capable strategist in his own right, known for his calm authority and good man-management.

Under Allison, Arsenal won another league title in 1934–35, playing a fast, attacking style that produced a then-record 115 league goals. He added a third championship in 1937–38 and won the FA Cup in 1936, defeating Sheffield United 1–0 at Wembley. These triumphs confirmed his status as one of the leading managers in English football.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought huge disruption. Competitive league football was suspended, and Allison’s role shifted largely to organising wartime fixtures, maintaining morale, and dealing with the logistical difficulties of losing players to military service. Arsenal’s Highbury Stadium was requisitioned as an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) centre, forcing the team to play home matches at White Hart Lane.

After the war, Allison returned to top-flight competition with an ageing squad and limited resources, but managed to keep Arsenal competitive. In 1946–47, his final season, the team finished 13th. He retired in the summer of 1947, passing the reins to Tom Whittaker, who had been his trainer.

George Allison left a remarkable legacy. His adaptability, media skills, and ability to manage in crisis cemented his place in Arsenal’s history. He died in 1957, remembered for a steady hand that kept the club successful through some of its most turbulent years.

Tom Whittaker (1947-1956)

Tom Whittaker managed Arsenal from 1947 until his untimely death in 1956, overseeing a post-war resurgence that brought two league titles and an FA Cup to Highbury. Born in Aldershot in 1898, Whittaker joined Arsenal as a player in 1919, initially appearing as a wing-half before a knee injury cut his playing career short. After retiring from the pitch, he retrained as a physiotherapist, qualifying as both a masseur and later a trainer, quickly becoming indispensable to the club’s off-field setup.

Whittaker’s expertise saw him serve as Arsenal’s first-team trainer under Herbert Chapman and George Allison, and he was integral to the famous “magnesium flare” physiotherapy techniques that pioneered modern sports medicine in English football. During the Second World War, Whittaker served as a major in the Royal Air Force, applying his experience to wartime physical rehabilitation.

When George Allison retired in 1947, Whittaker moved from trainer to manager, a rare leap in English football at the time. He made an immediate impact, securing the First Division championship in his debut season (1947–48), with a team renowned for its attacking flair and tactical discipline. His management style was built on empathy and respect, coupled with an emphasis on physical conditioning and player welfare, earning the enduring loyalty of the squad.

Whittaker led Arsenal to further silverware: the FA Cup in 1950 and a second league title in 1952–53, the latter secured on goal average after a nail-biting season-long race with Preston North End. His signings, including Joe Mercer and Jackie Henderson, refreshed an ageing squad and kept Arsenal at the top of English football despite post-war challenges.

Whittaker’s amiable but authoritative approach won respect throughout the game, and his autobiography, “The Arsenal Story,” offered a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse at the club’s inner workings. Tragedy struck in October 1956 when he died suddenly of a heart attack while still in office, aged just 58.

Tom Whittaker is remembered as one of Arsenal’s greatest servants: a player, trainer, physiotherapist, and manager who contributed across four decades, left a legacy of innovation and achievement, and helped build the foundation for the club’s future successes.

Jack Crayston (1956-1958)

Jack Crayston, born in Grange-over-Sands, Lancashire on 9 October 1910, remains one of Arsenal’s key figures from the interwar and post-war years, contributing to the club as a player, coach, and manager across a 24-year association.

A strong, aerially gifted right-half, Crayston started his senior football journey at Ulverston Town, before stepping up to Barrow in 1928, then to Bradford (Park Avenue), where his power and presence in midfield caught wider attention. In 1934, despite nursing a broken wrist and leg, he was signed by Arsenal as a replacement for Charlie Jones. Crayston announced himself with a debut goal in a remarkable 8-1 win over Liverpool, immediately establishing himself in Arsenal’s first-choice XI. He was known physically for his height (over six feet tall), long throws, and notably large feet, requiring size 12 boots.

During the 1930s, Crayston was integral to Arsenal’s domestic dominance. He won league titles in 1934–35 and 1937–38 and lifted the FA Cup in 1936, supplementing those with a Charity Shield in 1938. Internationally, he earned eight England caps between 1935 and 1937, scoring once, and debuted in a 3-1 win over Germany.

Crayston’s playing career was heavily disrupted by the Second World War. He joined the Royal Air Force and continued to play in wartime matches, but a serious knee injury against West Ham United in 1943 forced his early retirement from the pitch. In total, he made 187 competitive appearances for Arsenal, scoring 17 goals before moving into coaching.

He became Tom Whittaker’s assistant at Arsenal in 1947. Following Whittaker’s death in October 1956, Crayston initially took over as caretaker, then permanent manager in December. He declined a lucrative offer from Hull City to lead Arsenal during a difficult period for the club, in which limited transfer opportunities and squad decline became issues. Arsenal finished fifth in his first season but slumped to 12th the next, suffering a humiliating FA Cup exit at the hands of Northampton Town. In May 1958, dissatisfied and unable to enact needed changes, Crayston resigned.

Crayston then managed Doncaster Rovers, serving as both team manager and later secretary-manager until his retirement from football in 1961. Afterwards, he ran a newsagent’s in Streetly near Birmingham. He passed away on Boxing Day 1992, aged 82, as Arsenal were held to a goalless draw with Ipswich.

Crayston’s legacy is that of a model professional whose best playing years were curtailed by war, but who won major honours with Arsenal both on and off the pitch, personifying the club’s values through an era of enormous change.

George Swindin (1958-1962)

George Swindin was Arsenal’s manager from 1958 to 1962, a familiar face already to supporters as one of the club’s legendary goalkeepers. Born in 1914 in Campsall, Yorkshire, Swindin joined Arsenal as a player in 1936 for £4,000 from Bradford City. Over 18 years, he made 297 league appearances, winning three First Division titles (1937–38, 1947–48, 1952–53), the 1950 FA Cup, and two Charity Shields, earning a reputation for his aerial ability and physical dominance in the box. Despite this, he was famously never capped by England.

Swindin’s managerial career began with success at Peterborough United, where he won three consecutive Midland League titles before Arsenal appointed him manager in the summer of 1958. His first season at Arsenal brought optimism, with the club finishing third in the First Division, but subsequent years saw steady decline. The team struggled for consistency, finishing 13th, 11th, and 10th and failing to mount serious challenges for trophies at a time when rivals Tottenham Hotspur claimed the Double. Although Swindin tried to revitalise the squad by signing talents like George Eastham and Tommy Docherty, Arsenal remained mired in mediocrity.

Swindin was not offered a new contract at the end of the 1961–62 season, bringing to a close a managerial stint often remembered as part of a wider era of stagnation for the club. After leaving Arsenal, he managed Norwich City briefly, then spent time at Cardiff City, Kettering Town, and Corby Town, before retiring from football. Swindin lived out his later years away from the game, running a garage in Corby and later spending time in Spain before returning to England. He passed away in 2005, aged 90.

As a player, Swindin’s legacy at Arsenal is secure—one of the club’s best-ever goalkeepers, present for three championship teams and a pivotal period in Highbury’s history. As a manager, his time is remembered for a promising start overtaken by the club’s wider difficulties in a changing football landscape.

Billy Wright (1962-1966)

Billy Wright managed Arsenal from 1962 to 1966, stepping into the role after a celebrated playing career with Wolverhampton Wanderers and England. As a player, Wright was an inspirational leader and the first footballer in the world to reach 100 international caps, captaining both club and country with quiet authority and professionalism.

Arsenal’s board turned to Wright after parting ways with George Swindin, aiming for a high-profile figure to rejuvenate the club. Wright’s first season showed promise, with Arsenal finishing seventh in the First Division and qualifying for their first European campaign in the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. He made bold signings, including centre-forward Joe Baker, and oversaw the emergence and recruitment of several key young players such as Bob Wilson, Frank McLintock, John Radford, Peter Simpson and Peter Storey, many of whom would become pillars of Arsenal’s future Double-winning side under Bertie Mee.

Despite this encouraging start, the team’s league form weakened over the next three years, with finishes of eighth, thirteenth and fourteenth. Results in the FA Cup and European competition were similarly uninspiring, and crowds at Highbury dwindled, with a record low attendance of 4,554 recorded during his final season. Wright’s sides were noted for having attacking quality – Joe Baker and Geoff Strong, for instance, scored prolifically in the early years – but defensive frailty and inconsistency undermined progress. Commentators and former players alike have remarked that Wright was “simply too nice for the job,” lacking the ruthlessness, tactical authority and edge needed for managerial success at a club the size of Arsenal.

Football writer Brian Glanville summed up the consensus on Wright’s time in charge: “he had neither the guile nor the authority to make things work and he reacted almost childishly to criticism”. After four seasons, Wright was dismissed in the summer of 1966, making way for Bertie Mee.

Though often cited as one of Arsenal’s least successful modern managers by win percentage, Billy Wright’s legacy is more nuanced. He oversaw significant changes in youth recruitment and promotion, giving debuts and guidance to some of the players who would drive Arsenal’s success in the following decade. After leaving Arsenal, Wright focused on a successful broadcasting and administrative career in television, staying close to the sport before his death in 1994.

Wright’s time at Arsenal is remembered as a period of transition, marked by class and good intentions, but also by a recognition that greatness as a player does not always translate to managerial success.

Bertie Mee (1966 – 1976)

Bertie Mee managed Arsenal from 1966 to 1976, overseeing one of the most transformative and ultimately successful periods in the club’s history. Born in 1918 in Bullwell, Nottinghamshire, Mee trained as a physiotherapist after a short playing career with Mansfield Town was cut short by injury. He joined Arsenal in 1960 as club physio, renowned for his attention to detail and methodical approach.

In 1966, after Billy Wright’s departure, Arsenal took the unusual step of appointing Mee, then still the physiotherapist, as manager. He initially accepted only on the condition that he could return to his previous role if he was unsuccessful. Arthur Milton and Don Howe were brought in as his coaches to handle the footballing side, with Mee as an overseer and organiser.

Mee’s early years were spent rebuilding belief and structure. He promoted from within, giving responsibility to young players like Charlie George, Ray Kennedy, and Pat Rice, while also recruiting talent such as George Graham and Frank McLintock. He set new standards for discipline and fitness, fostering a club culture built on hard work, team unity, and tactical organisation.

These methods produced fast results. Arsenal reached their first League Cup finals in 1968 and 1969 but lost both. Undeterred, Mee’s side achieved a remarkable breakthrough in 1970, lifting the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup—the club’s first-ever European trophy, after defeating Anderlecht over two legs. The next season, Arsenal ended a 17-year wait for the league title and secured a historic Double, winning the First Division championship and the FA Cup in 1970–71. That FA Cup triumph against Liverpool, decided by Charlie George’s famous extra-time strike, remains one of Arsenal’s most iconic moments.

Mee managed Arsenal through a period of rapid change in English football. He placed heavy emphasis on collective effort over individual stardom. The Double-winning side was built on resilience, defensive solidity, and a spirit of togetherness that came to define his era. The likes of Bob Wilson, Pat Rice, Frank McLintock, and George Armstrong became club legends under his stewardship.

However, sustaining that high proved difficult. The following years brought a gradual decline, with the break-up of the Double side, generational transition, and increasing dressing room tensions. Mee’s strict management style became a source of friction, especially as results waned. Arsenal reached three consecutive FA Cup finals from 1978 to 1980 under future management, but only after Mee’s tenure ended following a disappointing 17th-place finish in the league in 1975–76.

After stepping down in 1976, Mee returned to medicine, later working as a hospital administrator. He passed away in 2001.

Bertie Mee is remembered as the man who rebuilt Arsenal into a modern, major force—delivering the club’s first Double through discipline, innovation, and meticulous planning. Though sometimes regarded as an “outsider” to football’s traditional management ranks, his legacy endures in the standards and culture he created.

Terry Neill (1976-1983)

Terry Neill was one of the most significant figures in Arsenal’s 20th-century history, serving both as captain and later as manager. Born in Belfast in 1942, he was signed from Bangor in 1959 and quickly established himself at Highbury, making his first-team debut at 18. By the age of 20, Neill became Arsenal’s youngest-ever captain, a record that still stands, ultimately amassing 275 appearances and scoring ten goals for the club. He also captained Northern Ireland, earning 59 international caps and famously scoring the winning goal when Northern Ireland defeated England at Wembley in 1972.

Neill left Arsenal in 1970 and became player-manager at Hull City, before moving to manage Tottenham Hotspur. In July 1976, Arsenal appointed him manager at just 34, making him the youngest boss in the club’s history. Neill’s impact was immediate and enduring. With new arrivals such as Malcolm Macdonald and Pat Jennings, and emerging talents like Liam Brady and Frank Stapleton, he reinvigorated the team and guided Arsenal into a new era of prominence.

His tenure was defined by consistent cup success. Arsenal reached three consecutive FA Cup finals between 1978 and 1980, securing an unforgettable victory over Manchester United in 1979, when Alan Sunderland’s last-minute winner sealed a dramatic 3–2 triumph. In European competition, Neill led the Gunners to the final of the 1980 Cup Winners’ Cup, with a landmark semi-final victory over Juventus in Turin, though Arsenal fell to Valencia on penalties in the final.

While the club’s cup runs stood out, Arsenal frequently fell short in the league during this period, partly due to the premature retirements and departures of key players. Nevertheless, Neill engineered a third-place finish in 1980–81, the club’s best in a decade, and continued to attract major signings, such as Charlie Nicholas from Celtic.

Neill was dismissed in December 1983 after seven years as manager and subsequently retired from football aged just 41. He later became a successful business developer, worked as a pundit and commentator, and ran sports bars in London. His death in 2022 was widely marked by tributes from Arsenal, Tottenham and the wider football world, reflecting his enduring popularity and the affection in which he was held by fans and colleagues alike.

Terry Neill’s legacy is assured: he was a transformative figure whose leadership on and off the pitch helped shape Arsenal’s modern era.

Don Howe (1983-1986)

Although for those of an older generation, Don Howe was associated primarily with West Brom (voted one of their greatest ever players) and England, he served the Gunners with distinction, firstly as a player and then more notably as first team coach (twice) and manager.

After a glowing career (including an FA Cup win under influential boss Vic Buckingham) at West Bromwich Albion, the Wolverhampton born right-back was brought to North London in 1964 for £42,000 by the universally respected, but ultimately unsuccessful Billy Wright, one of his heroes as a teenager. The ex-England captain immediately made his ex-international colleague Howe his club captain, but despite 74 appearances for the club at what should have been his peak, his career was prematurely ended by a badly broken leg after just two years at Highbury.

However, his coaching potential had already been noted, and he soon found himself in charge of the reserve team, before stepping up to be chief coach under the new manager, Bertie Mee, after Dave Sexton left to manage Chelsea in October 1967.

In all the current conversation about ‘losing the dressing room’ it is worth recalling how many of the Arsenal players at the time were unimpressed by the prospect of Howe when he replaced the respected Dave Sexton. Don took the challenge straight on and won them over with his knowledge and force of personality.

Having won his first battle as a senior coach, he was made assistant manager in March 1969. Just over a year later the Gunners won their first-ever European trophy, the 1970 Fairs Cup and followed that with a magnificent league and cup ‘double’ the next season.

Plenty within the game have stated that Bertie Mee’s 1971 double-winning side, and to a lesser extent Terry Neil’s end of the decade cup specialists, owed more to the background work done by Howe that the capacity of the men in charge. Certainly Charlie George suggested as much on several occasions, and there seems an obvious correlation between his departure from the club in the summer of 1971 to manage West Brom (“my greatest mistake”) and the rapid decline and break-up of the early 70s side. The fact that the team’s fortunes improved so much after his return in 1977 hardly seems coincidental.

When he returned to Highbury as Terry Neill’s chief coach in the summer of 1977, combining his role with the same position for England, (“I suppose in many ways I was happiest at Arsenal” he said at the time) he coached the team to three successive FA Cup finals – winning in 1979 – and the European Cup Winners’ Cup final in 1980.

Neill was sacked on 16th December 1983, with Arsenal in 12th place, after five defeats in six games. Don was made caretaker manager and having guided the team to 6th in the table, was appointed permanent Arsenal manager in April 1984. However, that was about as good as it got in what was to be a mixed couple of years, in a period of what can be most generously termed ‘transition’.

George Graham (1986-1995)

George Graham managed Arsenal from 1986 to 1995, marking one of the club’s most disciplined and successful eras. Born in Scotland in 1944, Graham was first an accomplished player at Arsenal from 1966 to 1972, winning the league and FA Cup double in 1971 and scoring 60 goals in 227 appearances for the club. After learning the ropes in management with Millwall, he returned to Highbury as manager at a time when Arsenal had fallen behind England’s top sides.

Graham quickly imposed strict discipline on and off the pitch, instilling a high standard for conduct and a focus on tactical rigour. He placed trust in young talent, most famously Tony Adams, who would captain a defence that became the envy of the country with Lee Dixon, Steve Bould, and Nigel Winterburn. Graham’s first season saw Arsenal finishing fourth in the league and lifting the League Cup after a 2–1 win over Liverpool.

He then brought Arsenal two league titles, the first dramatically won at Anfield in 1989 with Michael Thomas’s historic late goal sealing a 2–0 victory and the championship. The second came in 1990–91, with Arsenal losing just one league match all season. As cup competitions grew in prominence, Graham’s tactical shift towards even greater defensive discipline made Arsenal specialists in knockout football: his side completed a domestic cup double in 1992–93, winning both the FA Cup and League Cup, and followed up with the club’s second ever European trophy by beating Parma 1–0 to claim the 1994 Cup Winners’ Cup.

While often typecast for defensive football, Graham’s Arsenal teams of the late 1980s played attacking football that regularly saw them as one of England’s highest-scoring sides. His later sides did become more conservative, relying heavily on the prolific Ian Wright in attack.

Graham’s time ended in controversy in February 1995, when he was sacked after admitting to accepting an improper payment from an agent during a transfer. The FA imposed a year-long ban, bringing an abrupt halt to his Highbury career. In total, Graham won two league titles, an FA Cup, two League Cups, a Cup Winners’ Cup and several other honours, making him one of Arsenal’s most decorated managers and a foundational figure in the club’s modern history

Bruce Rioch (1995-1996)

Bruce Rioch served as Arsenal manager for just over a year, from the summer of 1995 until August 1996. His appointment came at a turbulent time: Arsenal were emerging from the shadow of George Graham’s departure and looking for a new direction.

Rioch arrived with a strong managerial reputation, having revitalised Bolton Wanderers and led them to promotion. At Arsenal, he quickly signalled a shift from Graham’s defensive mindset by encouraging a more attacking and fluent style of play. Under his management, Arsenal played a more positive brand of football, bringing freedom to a side previously defined by its rigidity.

Perhaps Rioch’s greatest legacy was the signing of Dennis Bergkamp, a move that would transform Arsenal’s fortunes not just for his own tenure, but for the club’s future under Arsène Wenger. Rioch played a key role in helping Bergkamp settle, with the Dutchman later saying he was “nursed, cajoled, and eased” into English football by the manager’s support, guidance, and his efforts to make Bergkamp’s family feel welcome.

On the pitch, Rioch steered Arsenal to fifth place in the Premier League, an improvement of seven places and 12 points on the previous season, securing a UEFA Cup spot. The side also reached the League Cup semi-finals. However, behind the scenes, Rioch’s forthright and demanding style clashed with senior players and the board. His insistence on discipline, directness in player relations, and a lack of political tact ultimately contributed to his brief tenure.

There were notable bust-ups, especially with top scorer Ian Wright, and a tense relationship with vice-chairman David Dein. Rioch sought greater financial backing for signings as he tried to modernise the team, but a dispute over transfer policy led to his abrupt sacking on the eve of the 1996–97 season.

Though his spell is often overshadowed by the club’s golden years that followed, Rioch’s management marked a bridge between eras. He opened the door for Arsenal to move beyond its defensive past, bedded in key players, and began to reform the club culture, making him an important, if short-lived, figure in Arsenal’s modern history.

Arsene Wenger (1996-2018)

Arsène Wenger managed Arsenal from 1996 to 2018, making him both the club’s longest-serving and most successful manager. His 22-year tenure revolutionised English football and transformed Arsenal’s identity, style, and ambitions.

Appointed in October 1996, Wenger arrived from Nagoya Grampus Eight in Japan, previously managing Monaco in France, winning Ligue 1 in 1988 and the Coupe de France in 1991. While some doubted the choice of a relatively unknown foreign manager, Wenger’s impact was immediate and profound.

Wenger’s first full season saw Arsenal win the Premier League and FA Cup double in 1997–98, an achievement they repeated in 2001–02. The pinnacle of his reign came in 2003–04, when Arsenal won the Premier League without losing a single league match – the ‘Invincibles’ season – a feat unmatched in modern English top-flight football. Under Wenger, Arsenal also embarked on a record 49 league matches unbeaten.

He led Arsenal to three Premier League titles and seven FA Cups, making him the most successful manager in the history of the competition. Wenger’s sides won seven Community Shields as well. His teams were renowned for their attacking football, technical quality, and ability to identify and nurture young talent. He converted the likes of Thierry Henry into world-class stars, discovered talents such as Patrick Vieira and Cesc Fàbregas, and championed an adventurous, passing-based style.

Wenger was pivotal in modernising English football. He introduced revolutionary approaches to sports science, player diet, recovery routines, and scouting, influencing not only Arsenal but the Premier League at large. He presided over the club’s move from Highbury to Emirates Stadium in 2006, prioritising financial stability at some cost to on-field competitiveness, and guiding Arsenal through a nine-year spell without silverware before resuming FA Cup success in the 2010s.

In total, Wenger managed 1,235 competitive games for Arsenal, winning 707 and posting a win percentage of 57.25%. The club also reached the Champions League final for the first time under his watch (2006).

Wenger’s later years were marked by increasing supporter impatience as Arsenal failed to challenge consistently for the league and finished outside the top four for the first time since his arrival due to the financial limitations due to building The Emirates. He announced his departure in April 2018, a year before his contract was due to expire. In his farewell address, Wenger said: “I am grateful for having had the privilege to serve the club for so many memorable years. I managed the club with full commitment and integrity. To all the Arsenal lovers, take care of the values of the club”.

Upon leaving Arsenal, Wenger took up the role of FIFA’s Chief of Global Football Development in 2019, leading initiatives to improve player development and the global structure of the game.

Wenger is remembered not only for his success but for the ethos he brought to Arsenal, blending results on the pitch with an emphasis on class, innovation, and long-term vision.

His legacy remains foundational for Arsenal and the modern Premier League.

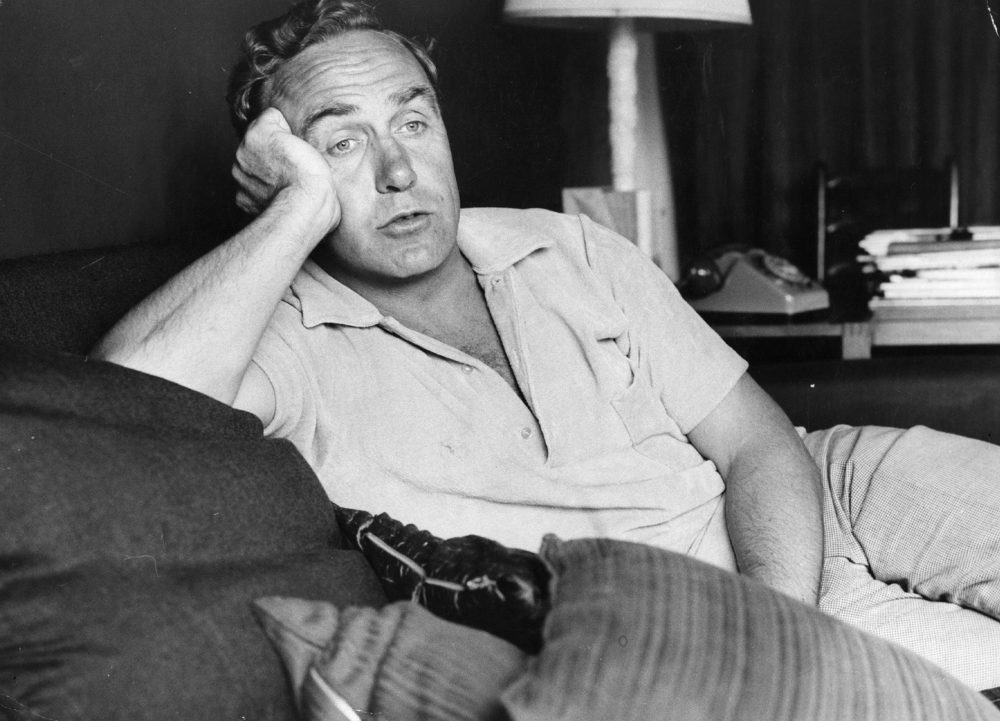

Unai Emery (2018 – 2019)

Unai Emery was Arsenal’s head coach from May 2018 to November 2019, taking charge in the immediate aftermath of Arsène Wenger’s long reign. Appointed for his pedigree in European competition, having won three straight Europa League titles with Sevilla and a domestic treble with Paris Saint-Germain, Emery arrived at Arsenal on a two-year deal, with an option for a third, at a pivotal moment for the club.

In his first season, Emery guided Arsenal to a 22-game unbeaten run and took the team to the 2019 Europa League final, only to lose 4–1 to Chelsea. Domestically, the club finished fifth in the Premier League – just outside the Champions League spots, missing out after a poor run in the final weeks of the campaign. He made notable signings, including record buy Nicolas Pépé for £72m, as well as Kieran Tierney and David Luiz, but the side’s defensive weaknesses persisted and the team was often criticised for lacking cohesion and identity on the pitch.

Emery’s second season unravelled early. Despite additions and high hopes, Arsenal’s form declined: the club struggled for results and displays were plagued by tactical uncertainty and frequent changes to line-ups and systems. Seven games without a win, the worst such run since 1992, prompted his dismissal in November 2019, just 18 months into his tenure.

Statistically, Emery’s record remains better than often remembered: a win percentage of 55% places him third among Arsenal managers with at least 20 games in charge, behind only Joe Shaw and Wenger. However, he was criticised for failing to address longstanding flaws, particularly the team’s defensive fragility and inconsistent mentality, which remained unresolved by the time of his departure.

Emery’s time at Arsenal is generally seen as having come at an awkward moment, with the squad in transition and off-field uncertainty affecting results. He has since rebuilt his reputation, most notably by winning the Europa League with Villarreal and leading Aston Villa to their best finishes in decades, which has led some to reassess his legacy in north London.

Mikel Arteta (2019-present)

Mikel Arteta has been Arsenal’s manager since December 2019, transforming the club’s identity and steering it back towards the top end of English and European football. Born 26 March 1982, Arteta previously enjoyed a distinguished playing career, captaining Arsenal and winning two FA Cups before transitioning to management.

Arteta was appointed after the club sacked Unai Emery. A former player and captain of Arsenal between 2011 and 2016, Arteta left the club to join Pep Guardiola at Manchester City when he retired from playing.

Arteta spent three years as Guardiola’s assistant, where he was widely credited with contributing tactical insight and driving player improvement. He took charge at Arsenal amid instability in late 2019 and immediately set about instilling structure, discipline and a modern tactical framework inspired by his experiences at City and by mentors such as Arsène Wenger.

He was initially set to follow Arsene Wenger at Arsenal but Raul Sanllehi convinced the board at the last minute to go with Emery, a client of a close friend of his.

In March 2020, Arteta was the first in the Premier League to test positive for Covid-19 after Arsenal played Olympiacos, prompting a country-wide shut down of football that lasted just over three months.

When his side returned, he guided Arsenal to an FA Cup and Community Shield victory in what was, effectively, his first five months of senior management.

The next two years were marked by rebuilding. Arsenal underwent significant squad turnover, promoted a new generation of talented academy products, and developed a distinctive, high-intensity playing style. Results initially were inconsistent, with two eighth-place league finishes, but marked progress saw Arsenal return to the Champions League for the 2023–24 season after a dramatic second-place finish in the Premier League in 2022–23, the club’s highest league placing since 2016 and their largest points tally since the “Invincibles” season.

Arteta’s 2023–24 side pushed Manchester City all the way in a fiercely contested title race, finishing just two points shy despite a club-record 28 wins in a 38-game league season. In 2024-25, they again finished second – this time to Liverpool, while they also reached the semi-final of the Champions League, thrashing Real Madrid on the way.

Under Arteta’s leadership, Arsenal have also won the Community Shield for a third time (2023). He has repeatedly been named Premier League Manager of the Month and was awarded London Football Awards Manager of the Year as Arsenal broke records and reasserted themselves among Europe’s elite.

At the time of writing in August 2025, Arteta’s tenure has delivered a 58% win rate across over 300 matches managed, the best by any Arsenal manager over such a span. He is credited with restoring Arsenal’s competitive DNA, developing stars such as Bukayo Saka, William Saliba and Martin Ødegaard, and consistently challenging for major honours.

In September 2024, he signed a three-year contract extension, reaffirming Arsenal’s commitment to him as the leader of the club’s continued resurgence

Arteta has been married to the Argentine-Spanish actress, television host, and model Lorena Bernal since 2010.

The couple have three children: Gabriel (born 2009), Daniel (born 2012) and Oliver (born 2015).