Before Arsène Wenger revolutionised Arsenal, he spent two years in Japan managing Nagoya Grampus Eight.

Disillusioned with French football following his dismissal from Monaco, Wenger was wary of the sport’s integrity after the Marseille match-fixing scandal in 1994, which had severely impacted his former club. But his next move remained uncertain.

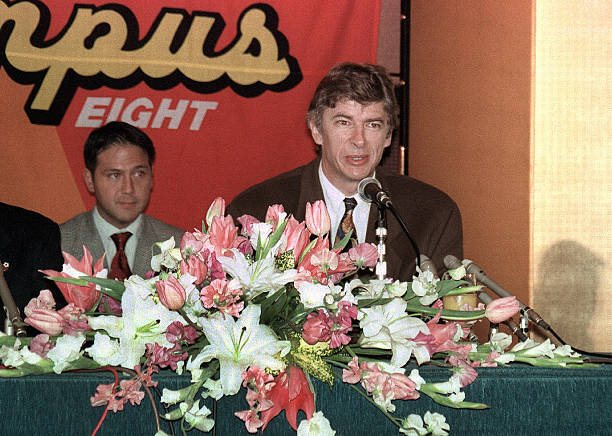

Toyota, owners of Nagoya Grampus Eight, approached him with an offer. Wenger, however, was not immediately convinced. It took two months of deliberation, consultation with friends and family, and a trip to Japan to watch the team before he finally agreed to take the job in December 1994.

Japan was not entirely disconnected from European football – Gary Lineker had played for Nagoya Grampus Eight from 1991 to 1994, retiring just as Wenger arrived. Despite his presence, the club had been woeful, finishing eighth in the first stage of the 1994 J. League season and dead last in the second. Wenger was inheriting a team in crisis.

His first move was to bring in Boro Primorac as his assistant, a man he deeply respected for his integrity. While managing Valenciennes, Primorac had refused to stay silent about match-fixing, exposing a scandal that led to Marseille president Bernard Tapie’s imprisonment and the club being stripped of its Champions League title.

Rather than being commended, Primorac was ostracised from French football. Wenger, however, saw his bravery and ensured he remained in the game.

Recruitment followed. Wenger signed Alexandre Torres from Vasco da Gama, a bold move at the time, as scouting Brazilian players via television was uncommon. He also secured Franck Durix from Cannes and Gérald Passi from Saint-Étienne, two midfielders suited to his technical philosophy.

Results, however, did not come immediately. Nagoya Grampus Eight suffered a string of defeats. Frustrated, Wenger challenged his players to take responsibility. When some sought guidance on training methods, he responded: “Decide for yourself. Why don’t you think it out?” His demand for autonomy and intelligence was unfamiliar to them.

Gradually, his methods took hold. The team climbed to fourth place by the end of the first stage. Wenger then took them to Versailles for a 14-day mid-season training camp, designed to build mental resilience and enhance creativity. When the J. League resumed, they won ten consecutive home matches. Dragan Stojković, who had previously struggled with discipline, flourished under Wenger’s guidance and emerged as one of the league’s standout players.

By season’s end, Nagoya Grampus Eight had surged to second place, a stunning turnaround from finishing bottom the previous year. Wenger was named Manager of the Year, while Stojković was voted Most Valuable Player.

Then came silverware. Nagoya Grampus Eight won their first major trophy, claiming the Emperor’s Cup with a 3-0 victory over Sanfrecce Hiroshima. Wenger had delivered the club’s first taste of success. Months later, he secured the Japanese Super Cup, defeating Yokohama Marinos before a crowd of nearly 40,000 fans.

His work did not go unnoticed. David Dein, who had been monitoring Wenger for a year, finally convinced Arsenal’s board to appoint him. But Wenger, ever the professional, refused to break his contract. He oversaw a six-match winning streak, guiding Nagoya Grampus Eight to second place before delivering a farewell speech in Japanese to the club’s supporters.

His legacy endured. Years later, Stojković returned as Nagoya Grampus Eight’s manager in 2008 and led them to their first J. League title in 2010, a managerial philosophy shaped by Wenger’s influence.

Japan left a profound mark on Wenger. “It helped me a lot to go to Japan, where I was manager of Grampus Eight. Everybody there is controlled. They laugh at you if you show emotion,” he later explained, attributing his composed demeanour to his time in Japan. He also transformed Arsenal’s dietary habits, inspired by Japanese nutritional practices. “I think in England you eat too much sugar and meat and not enough vegetables,” he once noted.

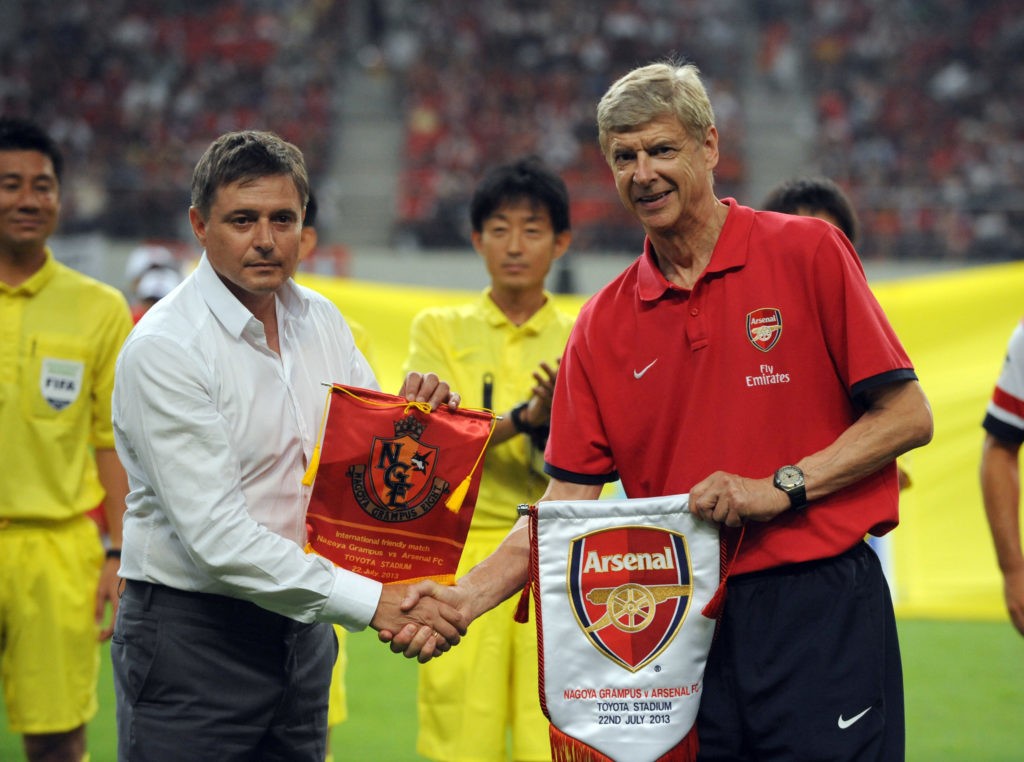

In 2013, Wenger brought an Arsenal squad to play Nagoya Grampus Eight in a preseason friendly. Ryo Miyaichi, a local-born Gunner, scored in front of 45,000 fans, a testament to the deep-rooted connection between Wenger and the club where he first honed his ideals.

The footballing world remembers Arsène Wenger for his Arsenal legacy, but it was at Nagoya Grampus Eight that the ideals defining his career – technical excellence, mental fortitude, and the relentless pursuit of beauty in football -were forged.